INTRODUCTION

In rural South African communities, young women who are mothers rely on networks of kin (sisters, parents, and aunts) to provide childcare in their absence (see Cassidy, 2019; Burman, 1995; Cantilon, Moore & Tesdale et al., 2021). Women, particularly those who are poor and unemployed, rely on their mothers, who, despite their advanced age, undertake childcare for them. There is a need to understand childcare-giving dynamics in these rural areas to inform policy and strategies for gender equality. Such a policy should aim to recognise and redistribute unpaid care work to ease the burden on women in rural areas. This paper investigates the intersection between child and elder care in rural areas, drawing from the lived experiences of grandmothers charged with looking after their grandchildren. The author also draws from her lived experience as a mother and someone who was also raised by a grandmother. Growing up in this context and coming from this background, as a researcher, she has unique insights into this topic.

The specific research questions that the paper focuses on are: In rural contexts,

- What are the reasons why childcare is undertaken by grandmothers despite their advanced age?

- What are some of the benefits and challenges of this form of childcare for both the child and the grandmother?

- How has climate change intensified the care burden?

- What form of support, if any, is given to grandmothers by the state in their roles as caregivers?

South Africa has not achieved universal access to health and education, with the result that most children in the villages are not in a formal preschoolor Early Childhood Development(ECD) centres (Shikwambane, 2023; Ilifa, 2024). The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 3 and 4 target good health and well-being, as well as access to quality education. South Africa is falling behind on both goals (UN, n.d.). In addition to the poor access to health and education, child poverty is a big problem in South Africa. According to Statistics South Africa (STATS SA 2021), in South Africa, 3 million of the 21 million children live below the poverty line, with children aged between 0 and 4 years being the hardest hit. Disturbingly, 23% of children in South African households experience hunger (UNICEF, 2024).

Child poverty has a spatial dimension, with children living in rural areas being hit hardest compared to those in urban areas (STATS SA, 2021). There are also racial differences in child poverty and deprivation, showing that children from the Black African population group (73.2%) are more likely to live in poverty compared to 43.6% of interracial children, 6.1% of white children and 20.1% of Indian children (STATS SA, 2021). More recently, the SDG country report (2023) notes that high levels of poverty, poor quality ECD programmes for children aged 0–4 years, and gender-based violence are still a serious challenge for development in South Africa.

According to Moore (2023), South African multi-generational households are characterised by diverse care arrangements. Sello et al. (2023) concur, noting that multiple childcare arrangements are common in South Africa. In poor resource-constrained environments, households tend to rely on the extended family for childcare, including children's involvement in care (Bray & Brandt, 2007). A practice also common in Namibia (Leonard et al., 2022). The childcare offered by kin in multi-generational households has a long history in African societies. Mathambo and Gibbs (2009) consider the role of the extended family in the care of children, especially the role of grandmothers. The unpaid childcare provided by co-resident grandmothers in multi-generational households, for example, is important as it allows mothers to participate in the labour market or to pursue further education. Existing in resource-constrained environments and relying on social grants, these households experience various socio- economic and environmental inequalities (Monasch & Boerma, 2004). In skip-generation households, households with only resident grandparents and grandchildren, research shows that grandmothers are playing an important role financially and psychosocially as household heads and caregivers (Cantillon et al., 2021). Cantillon et al. (2021) emphasise the contextual specificity of grandparental childcare. Elderly women need support in their role as caregivers, and any support given should centre on their lived experiences as caregivers and care recipients.

The care economy concept is a useful way to conceptualise the distribution of care work across society. The care economy, which comprises the unpaid care work performed in households and communities as well as jobs in the paid care sector and domestic work (UN Women, 2021), shows who ultimately carries the burden. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), globally, the unpaid care work carried out by women in households and communities, amounts to 11 trillion, 9% of global GDP (ILO, nd). Despite the role played by women, the state, through legislating welfare policies and implementing fiscal policy that funds crucial sectors, can re-shape the distribution of care in society.

For women in rural settings, converting unpaid care work into subsistence is complicated by climate change. Sub-Saharan Africa is considered a climate change hotspot and is expected to heat at twice the global average; as a result, severe and extreme weather events like hurricanes, flooding and wildfires are predicted for the region (Thornton et al., 2008). In recent years, agricultural plots have been destroyed by climate change, destroying livelihoods for the majority involved in agriculture in particular rural women. As the intensity and frequency of droughts in the region increase, food security in rural areas is compromised. Beenie et al., (2025) discuss some of the climate change- induced gendered impacts on women in sub– Saharan Africa asincluding for example: worsening care burdens, a loss in agricultural livelihoods and food insecurity. These effects are particularly severe due to a lack of physical and social infrastructure that allows people to cope.

In South Africa, apartheid racial policies and the migrant labour system have historically shaped the distribution of care, resulting in Black women shouldering the burden of care (Kasan, 2023). Moore (2023) argues that in South Africa diverse care arrangements must be understood in the context of inequalities that remain in post-colonial settings where there is highly uneven access to material resources, poverty and limited social welfare provision. Thus, women's position in care relations reveals elements of differentiation based on socioeconomics, racial and class positions.

Elderly women have particular needs and the inadequate state provision of care leads to women being burdened with unpaid care work. In fact as shown by Zhong and Peng (2024), in most households, families prioritise childcare while eldercare is neglected and only attended to in a crisis. This results in significant vulnerabilities due to neglect of elders and simultaneously burdening them with childcare. Moore and Kelly (2024) advocate for a socio- political contextual lens to understanding elder care neglect and state failures that emphasises the state’s reliance on a familialist care regime and how it impacts the everyday personal relationships between paid and unpaid carers of older persons.

The reliance on family caregiving as an approach to meeting society’s crucial care needs results in care work remaining invisible, carried out by Black and migrant women (Shamase & Sekaja, 2025). This paper contributes a social reproduction approach to understand the childcare arrangements in rural communities such as Mafarana and the role of elderly grandmothers in the context of climate change.

To do this, the paper adopts an ethnographic approach where 12 interviews were conducted with grandmothers taking care of young grandchildren to understand the distribution of care arrangements, the challenges they faced, and the specific reasons why elderly grandmothers provide childcare for their grandchildren. Whilst statistics in South Africa (STATS SA, 2025) has focused on the number of children in the care of extended family members, these studies have not adequately focused on care arrangements and dynamics within these households to explain the socio- economic and socio-cultural factors driving them. This paper does exactly that, and by doing so, fills an important gap in the literature where there are few qualitative studies in South Africa that have focused on the intersection between childcare and elder care.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Theorising Unpaid Child Care: The Care Economy

The care economy comprises both paid and unpaid care work performed in households and communities primarily by women (Muller, 2019). In many societies in sub-Saharan Africa, women are still the main caregivers for children and the elderly. Women are also engaged in various unpaid activities such as cooking and cleaning, water collection and food processing. Significant gender inequalities mark underpaid care work, and rural provinces are among the most affected, with the highest gender disparity, possibly due to disparities in childcare infrastructure.

Adopting a social reproduction lens shows that this unpaid care work, largely invisible, is indispensable to societies and communities. In the first place, (i) it contributes to the reproduction of the next generation of workers and (ii) contributes to caring for the elderly and the sick. In fact, women’s unpaid care work subsidises capitalist low-wage regimes, and it is considered by Feminist scholars (Exploring Economics, 2016) as productive work, along with market work. The 3 R framework, originally developed by Diane Elson (2009) as a call to recognise, reduce, and redistribute, subsequently expanded by UN Women (2019) to include calls to revalue and reward care work, is in line with this thinking. Given that everyone benefits from the care work, it should be characterised as a public good and be properly resourced through the national budget.

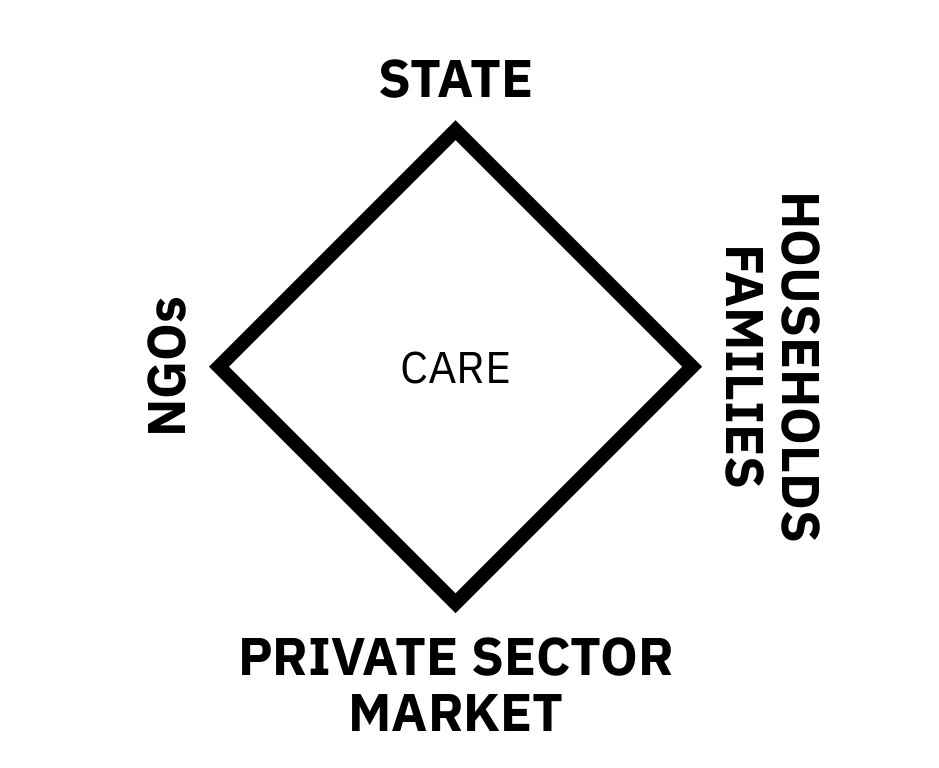

To understand the distribution of unpaid care work and who ultimately has the responsibility, in any society, we adopt the care diamond conceptualised by Razavi (2007). The care diamond maps out the distribution of care work among key actors and institutions within the macro-political space (Peng, 2019) and therefore how society arranges and finances care. The care diamond (see Figure 1) comprises households, the state, the private sector and non-government institutions, revealing not only the distribution but also the provision of care. By analysing the care diamond, we can determine who shoulders the most responsibility in care work, even though there is significant overlap in care responsibilities. Peng (2019) posits that the care diamond shows the institutional and policy configurations in society across various political regimes. It can, for example, show a political dispensation that relies more on market solutions rather than the state by reducing funding to state-provided care.

In South Africa, care has historically been shaped by apartheid policies, particularly the migrant labour system that regulated the flow of labour in and out of the native reserves (Kasan, 2023). The migrant labour system facilitated the outward migration of males of working age, leaving Black women in the rural countryside to care for children and the elderly. The result of the policy was a racialised and gendered care regime where Black women shouldered the unpaid care of those left behind (Kasan, 2023). Another dynamic that has shaped the care regimes in South Africa is the inflow of migrant women workers from neighbouring countries such as Zimbabwe and Lesotho (ILO, 2024). This has tended to reinforce the position of Black women in the racialised care regime. The end of apartheid did not lead to an undoing of these patterns. Instead, as Kasan (2024) argues, the care policy in South Africa post- apartheid, underpinned by neoliberal approaches adopted, a familialist approach, relying on vulnerable households.

Over the past decades, rural-to-urban labour migration rates among African women have increased in South Africa. Mthiyane et al. (2022) note that the mass inflow of economic migrants has strained government resources due to a lack of preparedness. Due to high unemployment, the economic migrants who find themselves in the urban areas become jobless and homeless, adding to the masses residing in the informal sector. Most of the Black women who migrated to the cities under apartheid found themselves employed in the care sectors as nannies and caregivers for white people (Gaitskell, Kimble, Maconachie, Unterhalter et al., 1983). Even though in post- apartheid South Africa, masses of Black women are also employed by the black middle-class as nannies, for these women, domestic work remains a nexus of a triple exploitation – by race, class and gender. Shai (2025) asserts that chronic underfunding and the state’s failure to invest in ECD have created a care deficit. This means that Black women who are employed as caregivers in the urban areas rely on kin, often their mothers or grandmothers, to take care of their own children back home.

Climate and environmental effects are exacerbating women’s unpaid care burdens (SCIS, 2024) and further reshaping unpaid care. Women in rural areas are engaged in two types of unpaid care work – direct care for persons and indirect care related to caring for the environment (Macgregor et al., 2022). Relying on women’s work means that climate change impacts make caring even more time-consuming for them. As climate change intensifies, it increases the care burden for both care for people - for example, grandmothers need to walk longer distances for water collection or alternatively reuse water. On the other hand, in these rural communities, women are regarded as environmental stewards, caring for the environment and animals. This often results in women being burdened with caring for the environment while also bearing the cost of environmental degradation.

Grandmothers as Key Actors: Intergenerational Childcare and the Role of Grandmothers

A higher percentage of African children in South Africa, compared to white, coloured and Indian children, live without their mother or father (African Health Research Institute, 2025) and in households where the grandmother is the primary caregiver. For example, among the various population groups in South Africa, only 32% of Black children are raised with their biological fathers at home. This is compared to 51% of Coloured children, 86% of Indian or Asian children and 80% of white children (STATS SA, 2018). Although South African children are far more likely to co-reside with their mother instead of their father, a significant number of them live with neither parent (STATS SA, 2019; Hatch & Posel, 2018). Monasch and Boerma (2004) consider orphanhood and childcare in South Africa and reveal that orphaned children are less likely to attend school and have higher multi- dimensional poverty rates compared to other children.

Increasing life expectancy in the face of an ageing population naturally raises care needs and increases the burden of care in any population (Himmelweit & Land, 2010). Combined with the rising cost of both child and elder care, this results in a care deficit, which means that a significant proportion of the population is vulnerable and without access to proper care. Although single parents face challenges in balancing work and the unpaid care of children, given the gender imbalances (Hatch & Posel, 2018) and the cultural expectation of childcare being a woman’s responsibility, women in South Africa make more sacrifices and are likely to drop out of the labour market due to childcare demands (Conolley, 1992; Floro & Komatsu 2011; Maurer-Fazio et al., 2011).

In South Africa, elderly women play a significant role as caregivers of young children, along with other female relatives in multi-generational households where parents are absent. According to STATS SA (2019), nationally, an estimated 39.9% of households are classified as nuclear, 34.2% as extended, and only 2.4% as complex households, meaning they contained non-related persons. While nuclear households were common with 1 or 2 children, extended households were most common in households with many children, more than 3. In poor multi-generational households in South Africa, research shows that grandmothers are playing an important role financially (relying on the old-age grant) and psychologically as household heads and assuming the role of breadwinner.

Mathambo and Gibbs (2009) discuss the African family as a dynamic network of individuals with mutual ties, including parents, children and grandparents as well as aunts and uncles. In this dynamic setting, individuals mutually care for each other, most prominently involving childcare by grandparents. In Igbo culture, for example, this practise is underpinned by the African philosophy of Ubuntu, and the belief that a child belongs to the community and society (Nnama-Okechukwu, Chukwu & Okoye, 2023). In this context, where family denotes an array of relations beyond biological parents and their children (Mathambo & Gibbs, 2009), there are benefits to co-resident childcare provided by a grandmother. Specifically, mothers of younger children benefit from childcare provided by grandparents, while the grandparents also receive companionship. Children are also materially better off (when left in the care of a grandparent than other relatives, especially where the mother is away for a prolonged period. Helle et al. (2024), for example, contend that investments by maternal grandmothers buffer children against the impact of adverse early life experiences. In Schrijner and Smits (2017), the effect of co- residing grandmother is positive for girls' schooling in sub-Saharan Africa. The caring for younger children by a grandmother benefits children growing up in the extended family (STATS SA, 2019), who also enjoy the benefits of growing up in close contact with other relatives, which enhances their socialisation.

There is also a reciprocal dynamic to these caring relations in that both the grandmothers and grandchildren benefit from each other’s companionship – grandmothers in dealing with their loneliness and grandchildren in receiving parental guidance, financial support, and emotional care. However, childcare by grannies adds to the grandmother’s physical and psychological burden. In poor rural households where resources are already stretched, this may lead to the prevalence of stress as grandmothers worry about making ends meet.

To the extent that elder and childcare intersect, significant vulnerabilities exist for the elderly. The neglect of elder care needs while simultaneously burdening them with childcare results in deficiencies in health and care outcomes.

RESEARCH METHODS: ETHNOGRAPHY

Mafarana Village

Mafarana is a village in the Greater Tzaneen municipality, located off the R37 road, 30 kilometres from the nearest town of Tzaneen. As a result of its location and distance from the nearest town, in recent years the village of Mafarana has witnessed a decline in its population as most people moved to the cities in search of employment. Like many villages in rural South Africa, in this village the main concerns are unemployment, poverty and lack of sanitation. Mirroring the general economic and social developments in South Africa a consistent thread throughout is, therefore, high youth unemployment (33%) coupled with high birth rates, leaving communities under severe socio-economic pressure.

The village of Mafarana is surrounded by commercial farms, which include some of the biggest citrus and avocado growers in the country, which employ most people in Mafarana, especially women. While this provides them with some income, the employment is characterised by precarity and exploitation. These seasonal workers, who are mostly female, do not have job security and benefits such as paid leave and childcare.

There is a distinct feminisation of subsistence agriculture that is undertaken by the elderly women whom I interviewed. Most of the women in the area are seasonal subsistence farmers growing crops such as maize, groundnuts, pumpkin, tomatoes and other indigenous plants. In this rural community, subsistence farming and collecting water take up a lot of the women’s time, but they are also engaged in other forms of unpaid work, such as childcare. This unpaid care work contributes to time poverty and reduced well-being. However, without this life-making and sustaining work, life in the rural countryside would not be sustainable; many households would largely go hungry.

Study Participants

If research is formed in the spaces between participants and the researcher (Browne, 2005), a view that assumes that the researcher is intimately involved with the subject of research, the researcher needs to acknowledge their standpoint about the study. The researcher was born in Mafarana village, where her paternal grandparents settled beginning in the early 1900s and where the researcher's father was born in 1950. Through her involvement with the community, the researcher has cultivated and nurtured unique relationships with the women in the area

This paper is based on data collected from 14 ethnographic interviews with grandmothers over the age of 50 who live with their grandchildren and are residents of Mafarana village. In addition to the grandmothers, key informant interviews were also held with the manager and caregivers of the Tiololeni elder pensions association of Mafarana. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the American University Ethics Board in August 2023. All participants provided signed informed consent prior to the interviews. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, all names have been replaced with pseudonyms (e.g., 'Granny 1').

A Tsonga speaking community member recruited the participants and initial participants were identified and approached; thereafter, snowball sampling was used to make referrals. The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide to allow the grandmothers to tell their stories, drawing from their lived experiences, and for the researcher to follow up on emergent issues. The discussions were audio recorded and later transcribed and translated into English.

The transcripts were subjected to qualitative thematic analysis to highlight the broader themes. An initial phase of open coding was conducted to identify recurrent concepts and ideas. These initial codes were then grouped into broader, more abstract themes (e.g., 'care work, reciprocity and love,' 'resources, financial strain and sacrifice,' 'climate-induced hardship and granny well-being'). This process was iterative, involving a constant comparison between the data and the emerging thematic structure to ensure the final themes were robustly grounded in the participants' narratives. The findings in the following section are presented with respect to the research questions identified.

- Who cares for children and why?

- What resources are available to grandmothers?

- What is the impact on grandmothers

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Nwana u vava e handle na le ndzeni (ka khwiri). Children are a pain before and after they are born.

Who Cares For Children And Why?

How did the grannies interviewed become caregivers for their grandchildren? A range of different circumstances resulted in the grannies assuming sole custody of the children. Most young parents in this community are unemployed or have moved away or migrated to the city to seek employment. “Vana va hina a va na mintirho” (Our children do not have jobs.) comments Granny 8, remarking on the joblessness in the area. ‘It is very sad,’ she says, ‘all her children are unemployed, and because of that, they rely on her.’ In this household, there are 3 children, a daughter-in-law married to her son and five grandchildren. Her son and the daughter-in-law are co-resident with their children because of their financial situation. Her two other children live in the household but periodically leave the household for lengthy periods of time to look for employment in Johannesburg. Similarly, most of the parents of the children in the care of their grandmothers are absent from the household due to annual migration to find work in the cities. These migrant labourers are still a part of the household as they travel back home once or twice a year. In fact, the homestead, which is referred to as ekaya, which has been passed on from one generation to the next, is a site of constant movement – for example, others moving out and others moving in.

Sometimes the parents of the children have died due to the HIV/AIDS pandemic leaving orphans behind (Rehle & Shisana, 2003). Orphaned children are the most vulnerable in the community due to the lack of a living parent and poverty associated with households where they reside. Within multi-generational households, childcare is distributed among the members, although it retains a gendered aspect, predominantly undertaken by women who are either a mother, a grandmother or a female relative. Even where fathers have sole custody because the mother is ill, has died or has abandoned the children, the fathers often rely on their own mothers for unpaid childcare.

Granny 2 and her husband are looking after twins who are 18 months old. Her husband assists with childcare, for example, driving the children to school and watching the children when the grandmother is not home. Despite this, the division of tasks is gendered, with the grandmother in charge of bathing, feeding and washing the children while the grandfather drives them to school and occasionally minds or plays with them when the grandmother is busy. Gender shapes all aspects, including sleeping arrangements, where the grandmother explains that she sleeps on the floor with the female child while her husband sleeps on top of the bed with the baby boy.

(i) Grandmothers perform childcare for their grandchildren as well as grandchildren of other kin, such as sisters

A common theme was that grandmothers perform childcare, most of the time as a sole or custodial caregiver of their grandchildren. Both maternal and paternal grandmothers undertake this role. For example, two of the grandmothers interviewed who were sole caregivers were also paternal grandmothers. The responsibility of childcare was also not limited to grandmothers caring for direct descendants. A grandmother (Granny 1) interviewed mentioned that she was caring for her sister's child, who was an orphan. The caregiving role also extends to the involvement of great-grandmothers where one great-grandmother over the age of 80 was undertaking childcare to assist her daughter- in-law. This intricate web of caregiving arrangements, in the context of the extended family, affirms the notion of kin is beyond biological or direct descendants.

There is a rich multi-generational network of women who see their role in childcare as extending beyond physical care. It encompasses the cultural work of socialising, teaching and imparting norms, customs and knowledge to the next generation. This is psycho-social and spiritual care work grounded in African epistemologies and ways of being. Tsonga grandmothers, for example, use oral storytelling to teach listening skills.

Grandmothers are entrusted with teaching children their genealogy, tracing it through the paternal line. Starting with the self and reading back to their origin, one read:

I am Basani, Basani wa Simon, Simon wa Shikwambana, Shikwambana wa…

Grandmothers often invoke the African philosophy of Ubuntu, “munhu i munhu hi vanhu” (A person is shaped by the community and cannot exist independently of the community that raised them). Ubuntu means that a person is a relational being, and to care for one’s descendants and offspring sustains communities. It emphasises interdependence, reciprocity, where care for persons and nature is intertwined. As a result of the social significance of this role, the grandmothers and great-grandmothers perceive their role to be important despite the challenges of ill health and poverty.

Sometimes children are abandoned and separated from their parents due to a parent remarrying. This exposes children to vulnerabilities and children can fall between the cracks, in a sense belonging nowhere when parents move on. When parents remarry it is usually up to the grandparents to take care of the child. Furstenberg and Cherlin (1991) find that most children adapt successfully as long as the mother does reasonably well financially and psychologically.

However, the declining relationship between the child and their father is usually the negative outcome of parental separation. A paternal grandmother (Granny 9), who is the caregiver of a 5-year-old grandchild, explains that the child's mother remarried, and her new husband rejected the child.

The child is here because that man does not want the child. The mother is unemployed and has two other children from a first marriage, so there is nothing she can do. She does receive the CSG, but I have never received anything.

On the other hand, the father of the child is living in another village and has his own family, so it was up to her to look after the child. “The father is also unemployed,” explains Granny 9.

(ii) Multi-generational living

In addition to grandchildren, most grannies live with some form of relative. Granny 3 and Granny 10 explain that they have raised many children, some of whom are adults and no longer in the household. This includes their own children, their siblings and their grandchildren, as well as cousins and in-laws. Granny 6 lives with two brothers and a sister, 2 children, and 5 grandchildren. Granny 6 mentioned that she is happy to care for her grandchildren since her own mother cared for her children in the same homestead. The homestead that she is referring to is a family home that has been in the family for years. She explains that the family home is a form of security for the children and grandchildren, ensuring that no one is ever homeless.

In the context of widespread unemployment, multi-generational living is a strategy to pool resources together. It is also a form of social protection in the absence of access to secure forms of employment and social welfare (Mtshali, 2015). Granny 8 explains that although the children are unemployed, they pool together whatever resources they have (income from part-time employment and social grants) to support the household.

(iii) Who else contributes to childcare?

Childcare takes place within a rich multi- generational network based on kinship, but also sometimes undertaken by friends and neighbours, underpinned by a community ethos. The childcare activities, such as watching and supervising children, extend beyond the boundaries of a single homestead. Many of the grandmothers remarked that there is always someone to keep an eye on the children in the village. Thus, grandmothers often rely on neighbours who are themselves grandmothers or mothers. One granny explains that when children come home, sometimes there is no one present, and thus neighbours help to keep an eye on them. However, “ni suka ni swekile…” (Before I leave the house, I ensure that I have cooked) so that the children can eat when they get back, and they know where to find the food. Granny 9’s younger sister came to the homestead to assist her with childcare after she underwent an operation. Without this unpaid childcare, paid work for most mothers would not be possible, explains a granny who works at a farm with her daughter. Granny 4 and her daughter are seasonal fruit pickers, and without this unpaid childcare, undertaken by the younger daughter, who is unemployed, they both would be unable to go to work.

What Resources Are Available To Support Grandmothers In Their Caregiving Role?

(i) Reliance on social grants

A lot of grandmothers in this area are struggling; my neighbour is in pain after she had an operation to remove a tumour… She has kids, but none of them live with her; no one really knows where the kids are. I am also poor, and it is very painful; we are all in pain (Granny 8).

As discussed earlier, grannies support families financially as the main caregivers of children in these households. Social grants constitute the main source of income for these households. The grannies who were eligible received an old age grant (OAG), which is a non-means-tested government grant for which South African citizens aged over 60 for women and over 65 years for men. At about R2100, it is not much, and in the majority of the households interviewed, the granny, who is also the household head, relies on this grant to support the family. Given that the OAG is the main source of income for unemployed and retired grannies, households where grannies are not eligible are extremely vulnerable. Granny 4 and Granny 6 are below the age of 60, the eligible age in South Africa to receive the Old Age grant. These grannies use income from their work as seasonal fruit pickers, as well as income for petty trading, to survive. Granny 6 explains:

The one who lives in the house uses grants to supplement the household income, but the other daughter receives a grant, and she’s never shared it with me. The money that I have, which I use to supplement the food budget, is money gained from my petty trading. My child, who lives outside, sends me money and helps with stock for petty trading.

As Granny 6 mentioned above, poor households use a combination of income and social grants. The child support grant (CSG), received by mothers of children below the age of 18, is also another important form of support to help meet children's needs. The CSG, which recently increased to R530, is one of the main forms of financial support in these households. Unlike the OAG, the child support grant is means- tested (This is calculated as 5 times the grant amount) and paid to the mother of the child, following the principle of following the child. In the households interviewed, most of the mothers, irrespective of whether they lived in the household or not, contributed to household expenses by sending this money to the caregiver (granny). However, in the case of another granny, she admitted that she doesn't know what her daughter does with the money because although she collects it, she doesn't contribute to childcare expenses, even though her child lives in the household. It is important to note that although the child grant is an important source of income, at R530 on its own, it is insufficient to meet the needs of the child especially given that it has not kept up with food inflation, and as a result, majority of children remain below the food poverty line (FPL) (Hall & Prudlock, 2024).

The CSG has been hailed as one of the most successful grants and means of poverty alleviation, saving children from malnutrition and stunting. Of the 20 million children in South Africa, just over 13.2 million receive the CSG every month (STATS SA, 2021). The conversations with the grannies interviewed show the key role it plays and the fact that it is indispensable. Indeed, together with state- provided healthcare and free education, what is termed the social wage, serves the majority of children’s needs, even if it is inadequate, says Granny 5.

According to Granny 6 not all the mothers who fail to send the money home are neglectful. She explains that her daughter works at a farm picking pepper and given that the income that she earns is not enough to even cover the transport to work, she uses the grant money to supplement the costs.

(ii) Other resources – Remittances

Some of the households interviewed had children working in Johannesburg and could thus send money home to support their children. Granny 2 explains that her husband receives his state pension as a retired policeman, and their mother sends money for their care to cover food, nappies and school. The grandmother looks after 18-month-old fraternal twins (a boy and a girl). She explains that her daughter works in the police force and every month is able to send money for school fees and has generous benefits, such as medical aid. Granny 3’s son works in Johannesburg and can send money on a regular basis to cover school fees and transport for his 6-year-old daughter. He sent the money through his younger brother, who is able to collect it for his mother.

Granny 3 commented on the high un- employment and clarified that she believes that if her son had a stable job, he would send some money home. He is just doing piece jobs, she explains. Granny 2 is looking after the children of her son and daughter, who are based in Johannesburg. She explains that her children don’t send her any money because they do not have secure jobs. Sometimes, the only thing that parents can afford to send home is the CSG. Granny 2 explains:

The CSG cards are with the parents of the children. My daughter can only afford to send the money from the CSG grant. My son and his wife said that they will send money when they receive it, since the card includes the younger children in their care; up to now, I have not received anything.

Granny 6 has a sister who is a police officer based in Johannesburg. Her sister routinely sends money to the household. She explains that what helps her is the support from their aunt: “She is the one who sent my daughter to school in Musina because I couldn’t afford the fees.”

(iii) Tiololeni elder care association – the role of the non-profit sector.

The care deficit amidst the crisis of care is seen more in rural areas where care infrastructure is generally lacking. There are no parks for children in Mafarana, only a few under- resourced state ECD facilities with the challenges of these centres being similar to the challenges facing the community, which are a lack of water, sanitation and electricity. In this context, the Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) sector plays a critical role and indeed, it is a lifeline for most grannies caring for younger children.

Tiololeni is an elder care organisation providing home based care, meals, recreation and education for grannies, based in Mafarana village. Most of the grannies interviewed are members of Tiololeni, and they mention the meals and support received from the non-profit organisation (NPO) as critical in the face of food insecurity. Granny 3 does not attend the sessions at Tioloeni, and she cites time poverty as a reason. She explains that she has a lot of work to do, for example, working in the field, cooking, cleaning and childcare. She is aware of the benefits; however, it is just not practical for her to attend. Granny 10 cannot walk the 400 metres to the community grounds where grannies meet because of her legs. She wants to attend and believes that being in the company of others would benefit her.

Impacts On The Grandmothers

(i) Grandmothers feel responsible.

The interviews reveal that grannies feel responsible for childcare, but they are under a huge strain. The childcare activities, such as watching and supervising children, feeding, washing and cooking, are physically demanding. Grandmothers, for example, complain of arthritic-pains and body aches. They also highlight the stress of managing conflict over resources within the households and negotiating survival on a daily basis. This is reflected in how most of the grannies will say,

I have nothing; I give them what I have.

Another granny who is raising a 2-year-old, 6- year-old and an 8-year-old (those are the youngest) says, if there is not enough food, I give it to my grandchildren.

Grannies often do not have much of a choice regarding their childcare responsibilities, given the poverty and lack of care infrastructure. Another granny explains that her daughter just gave birth so she had to come home so that she, her mother, can help her with the care of the infant. Another granny explained that the grandchildren came to stay with her because their mother was sick. Her older daughter is helping with the childcare responsibilities; she explained that although the current co- resident grandchildren are older, one being 14 years old and the other 8 years old, she has cared for other younger grandchildren before them. Although grannies do not seem to have much of a choice, it's important to highlight the role of agency and how they perceive this unpaid care work, as discussed below.

(ii) Childcare is not a burden but a labour of love.

Childcare is not a burden, even though most grandmothers are not healthy. They celebrate their role and see it as a labour of love, shaping the next generations. The grannies acknowledge that childcare is physically demanding, and most of the grannies are physically unhealthy and suffer from various ailments. Granny 2 and Granny 6 both complained about pain following a car accident. Granny 2 says that “mbilu hi yoho yi lavaka ku va hlayisa vana lava” (The heart wants to care for the children, even if the body is unable). Awareness of mental health issues is generally very low among them. However, Granny 2 reports that her mental health is good and mentions mental health benefits such as feeling happy and that their lives have meaning.

The grannies perceive childcare responsibilities as an activity that brings meaning to their lives and is a source of joy. Granny 6 mentioned that providing for the children is hard, but she still does it out of love and care. Granny 8 mentioned that she was depressed and anxious because she lost 2 of her children last year. She was advised not to self-isolate and encouraged to be around people. She noted that taking care of children is not easy, but she feels that it is her responsibility, and it has improved her mental health. Granny 8 mentioned that the kids were given to her; she just had to take care of them. As a grandmother, she feels good, but the child is still young, so there are no benefits, but she is happy.

CONCLUSION

Co-resident grandmothers in rural households are bearing the burden of unpaid childcare work, where the state has failed to provide care. Childcare within these households is gendered, embedded in multi-generational networks headed by elderly Black African women. There are several reasons why grannies undertake childcare for their grandchildren.

Unemployment, illness and death of parents and inadequate earnings to support children are some of the reasons. Despite the challenges with ill health, the childcare is not viewed as a burden, even though most grandmothers are not healthy. They celebrate their role and see it as a labour of love that shapes the next generations.

The findings of this paper show that South African rural households headed by black elderly women are vulnerable, impacted by climate change and poverty. These households eke out some form of survival using social grants and precarious forms of employment. Grandmothers for example rely on remittances, the OAG and the CSG to support the household. The state’s reliance on these households to provide unpaid care work is a major subsidy for the South African capitalist low wage regime economy.

What are the policy implications?

Grannies need financial, psychological and social support in their role as caregivers. This support should include a caregiver grant since both the OAG and the CSG are inadequate.

The triple R model provides a framework for thinking about redistributing and re-shaping unpaid care work among the main actors.

Better and more accessible care facilities, subsidised water and electricity can alleviate the burden of care on grandmothers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank Prof. Mieke Meurs from the Department of Economics, College of Arts and Sciences, American University, Washington D.C, for the funding to undertake this study received as part of the global scholars program, and for reviewing this paper numerous times; thanks for your insightful feedback. I would also like to thank Dr James Musonda, and the Southern Center for Inequality Studies (SCIS) collective for commenting on earlier versions of this paper.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

REFERENCES

Africa Health Research Institute. (2025). Realities of Fatherhood in South Africa today. https://www.ahri.org/realities-of-fatherhood-in-south-africa-today/

Beenie, A., Hoveni, J.B., Madhi, Y., Farr, V., & Ngcukana, L. (2025). A Care Approach to Achieving Gender Justice in Southern African Food Systems in the Context of Climate Change. Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ), Johannesburg, South Africa. https://iej.org.za/a-care-approach-to-achieving-gender-justice-in-southern-african-food-systems-in-the-context-of-climate-change/

Bray, R., & Brandt, R. (2007). Childcare and poverty in South Africa: An ethnographic challenge to conventional interpretations. Journal of Children and Poverty, 13(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10796120601171187

Browne, K. (2005). Snowball Sampling: Using Social Networks to Research Non-Heterosexual Women. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000081663

Burman, S. (1995). Childcare by the elderly and the duty of support in multigenerational households. Southern African Journal of Gerontology, 4(1), 13-17. https://journal.ru.ac.za/index.php/sajog/article/view/57/49

Cantillon, S., Moore, E., & Teasdale, N. (2021). COVID-19 and the pivotal role of grandparents: Childcare and income support in the UK and South Africa. Feminist Economics, 27(1-2), 188-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2020.1860246

Cassidy, J. (2019). Intergenerational Co-located Child and Eldercare. Tackling disadvantage through an assets-based approach to eldercare and childcare services. The Rank Foundation. https://media.churchillfellowship.org/documents/Cassidy_J_Report_2019_Final.pdf

Connelly, R. (1992). The effect of child care costs on married women's labor force participation. The review of Economics and Statistics, 74(1), 83–90.

Exploring Economics. (2016). Reproductive labour and care work. https://www.exploring-economics.org/de/entdecken/reproductive-labour-and-care/

Floro, S., & Komatsu, H. (2011). Gender and Work in South Africa: What Can Time-Use Data Reveal? Feminist Economics, 17(4), 33-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.614954

Furstenberg, F. F., & Cherlin, A. J. (1991). Divided families: What happens to children when parents part, 1. Harvard University Press.

Gaitskell, D., Kimble, J., Maconachie, M., & Unterhalter, E. (1983). Class, race and gender: Domestic workers in South Africa. Review of African Political Economy, 10(27-28), 86-108. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4005601?seq=1

Hall, K., & Prudlock, P. (2024). Child Support Grants. University of Cape Town (UCT). http://childrencount.uct.ac.za/indicator.php?domain=2&indicator=10

Hatch, M., & Posel, D. (2018). Who cares for children? A quantitative study of childcare in South Africa. Development Southern African, 35(2), 267-282. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2018.1452716

Helle, S., Tanskanen, A.O., & Coall, D.A., Perry, G., Daly, M., & Danielsbacka, M. (2024). Investment by maternal grandmother buffers children against the impacts of adverse early life experiences. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 6815. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-56760-5

Hernando, R. C. (2020). Unpaid Care and Domestic Work: Counting the Costs. APEC Policy Support Unit Policy Brief No. 43. https://www.apec.org/docs/default-source/publications/2022/3/unpaid-care-and-domestic-work-counting-the-costs/222_psu_unpaid-care-and-domestic-work.pdf

Himmelweit, S., & Land, H. (2010). Change, choice and cash in social care policies: Some lessons from comparing childcare and elder care(No. 74). Open Discussion Papers in Economics.

ILO. (2018). Care work and care jobs. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_633166.pdf

ILO. (2024). The labour market situation of women migrant workers in the SADC region. https://www.sammproject.org/wp-content/uploads/download-manager-files/The-Labour-Market-Situation-of-Women-Migrant-Workers-SADC-.pdf

Kasan, J. (2023). Engaging the care economy in the global south: debates and contestations. Working paper series no 1. Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ), Johannesburg. https://iej.org.za/engaging-the-care-economy-in-the-global-south/

Kasan, J. (2024). Mapping South Africas care regime pathways to a care focused social policy. Working paper series no 2. IEJ, Johannesburg. https://iej.org.za/mapping-south-africas-care-regime-pathways-to-a-care-focused-social-policy/

Leonard, E., Ananias, J., & Sharley, V. (2022). It takes a village to raise a child: everyday experiences of living with extended family in Namibia. British Academy,10(2), 239-261. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/010s2.239

MacGregor, S., Arora-Jonsson, S., & Cohen, M. (2022). Caring in a changing climate: Centering care work in climate action. Oxfam research report. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/caring-in-a-changing-climate-centering-care-work-in-climate-action-621353/

Mathambo, V., & Gibbs, A. (2009). Extended family childcare arrangements in the context of AIDS: collapse or adaptation? AIDS Care, 21(S1), 22-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120902942949

Maurer-Fazio, M., Connelly, R., Chen, L., & Tang, L. (2011). Childcare, eldercare, and labor force participation of married women in urban China, 1982–2000. Journal of Human Resources, 46(2),261-294. https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/4204/childcare-eldercare-and-labor-force-participation-of-married-women-in-urban-china-1982-2000

Monasch, R., & Boerma, J.T. (2004). Orphanhood and Childcare patterns in Sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of national surveys from 40 countries. Aids, 18, S55-S65. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200406002-00007

Moore, E. (2023). Family care for older persons in South Africa: heterogeneity of the carer’s experience. International Journal of Care and Caring, 1(aop), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1332/239788221X16740630896657

Moore, E., & Kelly, G. (2024). Struggles over elder care in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 41(6), 1062-1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2024.2374823

Mthiyane, D. B., Wissink, H., & Chiwawa, N. (2022). The impact of rural–urban migration in South Africa: A case of KwaDukuza municipality. Journal of Local Government Research and Innovation, 3 (0), a56. https://jolgri.org/index.php/jolgri/article/view/56/218

Mtshali, M. N. G. (2015). The relationship between grandparents and their grandchildren in the black families in South Africa. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 46(1), 75-83. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.46.1.75

Müller, B. (2019). The careless society— Dependency and care work in capitalist societies. Frontiers in Sociology, 3, 44. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sociology/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2018.00044/full

Nnama-Okechukwu, C. U., Chukwu, N. E., & Okoye, U. O. (2023). Alternative childcare arrangement in indigenous communities: Apprenticeship system and informal child fostering in South East Nigeria. Indigenization Discourse in Social Work: International Perspectives, 373-388. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37712-9_22

Peng, I. (2019). The Care Economy: a new research framework. Hal-03456901. https://sciencespo.hal.science/hal-03456901/

Rehle, T. M., & Shisana, O. (2003). Epidemiological and demographic HIV/AIDS projections: South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research, 2(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2003.9626554

Schatz, E., & Seeley, J. (2015). Gender, ageing and carework in East and Southern Africa: A review. Global public health, 10(10), 1185-1200. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1035664

Shamase, L. Z., & Sekaja, L. (2025). Mothering away from home: experiences of Zimbabwean domestic workers in South Africa. Frontiers in Sociology, 10, 1607624. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sociology/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2025.1607624/full

SCIS. (2024). The climate care nexus: a conceptual framework. Working paper number 70. Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, Johannesburg. https://climateandcareinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Working-Paper-70-Care-Climate-Nexus-Conceptual-Framework.pdf

Schrijner, S., & Smits, J. (2018). Grandmothers and children’s schooling in Sub-Saharan Africa. Human Nature, 29(1), 65-89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-017-9306-y

Sello, M., Adedini, S. A., Odimegwu, C., Petlele, R., & Tapera, T. (2023). The Relationship between Childcare-Giving Arrangements and Children’s Malnutrition Status in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032572

Shai, L. (2025). Unlocking affordable and quality childcare to benefit women, children, and the broader society: A review of the South African childcare system. Ilifa la bantwana, Johannesburg. https://ilifalabantwana.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Childcare-Report.pdf

STATS SA. (2018). https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14044

STATS SA. (2019). Families and parents are key to well-being of children. https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14388

STATS SA. (2020). South Africa’s poor little children. https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=13422

STATS SA. (2021). Trends in selected health indicators regarding children under 5 years in South Africa. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/03-00-16/03-00-162020.pdf

STATS SA. (2023). SDG goal country report South Africa. https://www.statssa.gov.za/MDG/SDG_Country_report.pdf

STATS SA. (2025). Millions of South African Children Raised by Grandparents. https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=18066

Thornton, P. K., Jones, P. G., Owiyo, T., Kruska, R. L., Herrero, M., Orindi, V., & Omolo, A. (2008). Climate change and poverty in Africa: Mapping hotspots of vulnerability. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 2(1), 24-44. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/663