INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Financial inclusion and banking stability are critical pillars of sustainable economic development, improved livelihoods, and systemic resilience. Financial inclusion enhances access to savings, credit, insurance, and payment systems—particularly for marginalised populations thereby fostering economic participation and social equity (World Bank, 2020; Allen, Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, & Peria, 2016). Banking stability, on the other hand, ensures that financial institutions can absorb shocks, maintain confidence, and sustain the investment necessary for long-term growth (Adrian & Shin, 2010; Bank for International Settlements, 2019).

Technological advances have accelerated financial inclusion in developing countries with limited banking infrastructure. Mobile money and digital financial platforms have notably expanded access, though they also pose new risks such as cyber threats and fraud (Mandić, Marković, & Žigo, 2025). The 2007–2008 global financial crisis underscored the importance of balancing inclusion with prudential regulation to safeguard systemic stability (Brunnermeier, 2009).

Despite global progress, substantial disparities remain. As of 2017, about 1.7 billion adults lacked access to formal financial services, with women and low-income groups in Sub-Saharan Africa being most affected (World Bank, 2022; Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, Singer & Van Oudheusden, 2015). Countries like Kenya and South Africa have achieved notable inclusion gains, whereas others, such as Burundi and Niger, remain heavily excluded (Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, Singer, Ansar & Hess, 2018). This unevenness reveals that while financial inclusion can strengthen stability through deposit mobilisation and risk diversification, weak oversight may amplify vulnerabilities (Tshuma, Tshuma, Mpofu & Sango, 2023).

In Zimbabwe, persistent exclusion remains a barrier to inclusive growth. According to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ, 2020), 23% of the population was financially excluded in 2014, prompting the launch of the National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS) in 2016. The strategy prioritises digital finance and outreach to marginalised populations, especially in rural areas. Yet, stark provincial disparities persist: Matabeleland North records a 60% exclusion rate, followed by Mashonaland Central (58%), Mashonaland East (53%), and Matabeleland South (50%), reflecting limited financial infrastructure, low literacy, and high poverty levels (Chivasa & Simbanegavi, 2016; Mhlanga, 2020). Conversely, urban centres such as Bulawayo (20%) and Harare (17%) enjoy better access due to higher incomes and proximity to financial institutions.

Source: Chivasa & Simbanegavi (2016), adapted from Zimbabwe National Financial Inclusion Strategy (2016), Mhlanga (2020a).

Figure 1 highlights clear regional disparities in financial exclusion across Zimbabwe, with rural provinces experiencing the most acute challenges. Matabeleland North, with an exclusion rate of 60%, reflects the compounded effects of limited financial infrastructure, low levels of financial literacy, and pervasive poverty, which together restrict access to formal financial services and economic opportunities. Mashonaland Central (58%), Mashonaland East (53%), and Matabeleland South (50%) also face significant exclusion, suggesting that residents in these regions encounter similar structural barriers that hinder financial participation. The persistence of such high exclusion rates indicates that without targeted interventions—such as expanding branch networks, promoting financial education, and addressing poverty—these areas will continue to lag in financial inclusion, perpetuating economic inequalities. In contrast, urban centres like Bulawayo (20%) and Harare (17%) demonstrate lower exclusion rates due to better infrastructure, higher incomes, and greater proximity to financial services, underscoring how geographic and socio-economic factors directly influence access to finance (Chivasa & Simbanegavi, 2016; Mhlanga, 2020).

These inequalities hinder inclusive economic growth and reinforce regional poverty traps. The Institute for Inclusive Social and Public Policy Research (IISPR, 2023) emphasises that expanding financial access in underserved regions is crucial for poverty reduction and resilience-building. Mutale and Shumba (2024) find that financial inclusion strengthens banking stability through enhanced deposit mobilisation and improved credit performance, particularly in rural areas. Similarly, Chivasa and Simbanegavi (2016) argue that expanding rural financial services reduces reliance on informal lenders and helps stabilise the formal banking system. Collectively, these findings underscore that improving access to financial services is both an inclusion and stability imperative—enhancing liquidity, reducing vulnerability, and fostering sustainable development.

Financial literacy is equally pivotal in this relationship. It promotes responsible borrowing, improves repayment behaviour, and strengthens overall financial stability (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018; Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt & Levine, 2007). Mutale and Nyathi (2024) further argue that inclusive financial policies targeting women, youth, and rural populations promote equity and reduce income inequality—key ingredients for economic and systemic stability. However, infrastructure deficits, low digital literacy, and high service costs continue to hinder progress, particularly in rural Zimbabwe (Mhlanga, 2020). Policy makers and financial institutions must therefore strengthen digital financial inclusion, improve regulatory frameworks, and invest in financial education to enhance both inclusion and banking stability (RBZ, 2022).

Research Objective

The primary objective of this study is to quantitatively examine the relationship between financial inclusion and banking stability in Zimbabwe using the Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) technique.

RELATED LITERATURE ON FINANCIAL INCLUSION AND BANKING STABILITY

Financial Inclusion: Definition and Overview

Financial inclusion refers to the accessibility and effective use of financial services by all households and businesses, especially the poor and small and medium enterprises (Yoshino & Morgan, 2016). The World Bank (2022) defines it as the availability of useful, affordable financial products—including payments, savings, credit, and insurance—delivered responsibly and sustainably. Similarly, the IMF (2015) and Atkinson and Messy (2013) highlight its role in improving economic well-being and resilience through financial education and empowerment.

According to the United Nations (2018), financial inclusion supports key development goals such as poverty reduction, social equity, and economic empowerment. Beyond accessibility, it also emphasises usability, affordability, and the ability to derive meaningful developmental outcomes (Patwardhan, 2018). Thus, financial inclusion operates not merely as a social policy instrument but as a macroeconomic lever for inclusive and stable economic growth.

Drivers of Financial Inclusion

Financial inclusion is driven by various factors. Technological innovations like digital payments, mobile banking, and fintech solutions help bridge financial gaps (GSMA, 2020). Supportive regulatory frameworks and consumer protection laws foster trust in financial systems (World Bank, 2018). Financial literacy programs increase awareness of financial products, while improved banking infrastructure—such as agent banking and mobile connectivity—expands access, particularly in remote areas (IMF, 2020). Access to microfinance, alternative credit scoring, and gender-inclusive business models also play key roles (Microfinance Gateway, 2017; UN, 2021).

Measuring Financial Inclusion

Measuring financial inclusion involves multiple indicators. Sarma (2008) proposes metrics such as the proportion of adults with bank accounts and bank branches per million people. The World Bank (2012) considers loan accounts per 1,000 adults a key indicator. Han and Melecky (2013) assess inclusion through deposit access and usage, while transaction volumes and household financial well-being provide additional measures (World Bank, 2015). Sarma’s (2008) index combines depth, availability, and service usage to create a more comprehensive measurement.

Benefits of Financial Inclusion

Financial inclusion is critical for economic development and poverty reduction. It enables individuals to manage risk, invest, and build resilience against financial shocks (World Bank, 2022). It also fosters economic growth, employment, and formalisation of the economy (Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, 2022). During crises such as COVID-19, financial inclusion facilitated access to emergency funds (UNSGSA, 2022). The United Nations Capital Development Fund [UNCDF] (2022) highlights its role in achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including poverty eradication, gender equality, and economic stability. By integrating underserved populations into formal financial systems, financial inclusion strengthens financial stability (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022).

Determinants of Financial Inclusion

Key determinants of financial inclusion include physical accessibility, financial literacy, technology, trust, and outreach (Kabakova & Plaksenkov, 2018). In Zimbabwe, gender, education, income levels, and trust significantly influence financial inclusion (Barugahara, 2021). Studies in Peru (Camara, Peña, & Tuesta, 2014) and Africa (Allen, Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, & Pería, 2012) emphasise the role of education and mobile banking in increasing financial participation. Technology, particularly digital banking and mobile money services, plays a crucial role in expanding access (Ramakrishna & Trivedi, 2018).

Barriers to Financial Inclusion

Despite progress, barriers remain. Gwalani and Parkhi (2014) identify high service costs and inadequate technology in India. Similarly, Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance (2014) notes demand-side barriers like low financial literacy and supply-side challenges such as distance and complex banking procedures. In Sub-Saharan Africa, Ulwodi and Muriu (2017) found geographical barriers, cost, and literacy to be major impediments. In Zimbabwe, financial illiteracy, lack of formal identification, and high transaction costs hinder inclusion (Barugahara, 2021). The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (2020) highlights additional challenges such as mistrust and inadequate documentation among women, youth, and rural populations. Addressing these barriers is crucial for enhancing financial inclusion.

Bank Stability

Banking stability refers to the ability of the financial system to withstand internal and external shocks while maintaining its core functions (European Central Bank, 2019). The World Bank (2022) defines financial stability as the absence of systemic crises, emphasising resilience under stress. A stable financial system efficiently allocates resources, manages risks, sustains employment, and maintains price stability.

A stable banking system also fosters economic growth by promoting trust, ensuring efficient resource allocation, and maintaining confidence in financial institutions (Bhattacharya & Thakor, 1993). Novotny-Farkas (2016) views stability as a continuum, where financial elements interact to sustain systemic integrity. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (2022) emphasises the need for strong regulatory frameworks to support financial stability.

Theories Linking Financial Inclusion and Stability

The relationship between financial inclusion and bank sector stability is grounded in several theoretical perspectives from financial economics, institutional theory, and risk management.

Financial Deepening and Economic Growth

Financial inclusion expands access to financial services, fostering financial deepening by increasing the deposit base and diversifying bank risk. A more inclusive financial system enhances stability, particularly in emerging economies like Zimbabwe, where a larger depositor base strengthens banks against liquidity shortages (Honohan, 2008; Beck et al., 2007).

Financial Intermediation Theory

Diamond and Dybvig (1983) emphasise the role of financial institutions in facilitating savings and investments, promoting risk-sharing and stability. Financial inclusion bolsters banks by attracting deposits and expanding credit access, stimulating economic activity. However, rapid expansion, if poorly managed, can heighten system vulnerabilities. Stability improves when banks rely on a diversified deposit base to fund long-term loans, reducing liquidity risks (Greenwood & Jovanovic, 1990). In Zimbabwe, inclusive financial services are crucial during economic instability to prevent banking crises.

Stability vs. Inclusion Trade-off Theory

Khan (2011) and Sahay et al. (2015) highlight a trade-off between financial inclusion and banking stability. While increased access fosters economic growth, it can also elevate systemic risks if it leads to excessive credit expansion and weaker lending standards. Serving high-risk borrowers may expose banks to liquidity challenges, potentially undermining financial discipline. Thus, achieving financial inclusion without compromising stability requires prudent risk management.

Financial Inclusion and Bank Stability

Numerous studies have examined the relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability. Research by Danjuma (2018) and Morgan and Pontines (2014) suggests a positive link between these two variables. However, Amatus and Alireza (2015) found a mixed impact, noting that while bank deposits negatively affect stability, loans contribute positively. Morgan and Pontines (2014) further identified three key ways in which financial inclusion enhances stability: (1) diversification of bank assets through increased lending to smaller firms, which reduces risks in loan portfolios and lowers financial system interconnectedness; (2) stabilisation of the deposit base by incorporating more small savers, thereby reducing reliance on volatile non-core funding; and (3) improved monetary policy transmission, which strengthens financial stability.

Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability: A Review

Hannig and Jansen (2010) argue that including low-income groups in the financial system stabilises deposit and loan bases, enhancing resilience, as these groups are relatively insulated from economic cycles. Similarly, Prasad (2010) highlights that credit access for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) promotes employment and economic stability. However, Khan (2011) cautions that expanding credit access without robust lending standards can trigger crises, as seen during the U.S. subprime mortgage collapse, while poorly regulated microfinance institutions may further undermine stability.

Empirical studies report mixed results. Jungo, Madaleno, and Botelho (2022) found that financial inclusion enhances stability in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, particularly when strong regulatory frameworks exist. In Jordan, Al-Smadi (2018) applied the Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) method, showing a weak positive link between financial inclusion and stability, though risks from domestic credit expansion and global crises persist.

Broader access to deposits reduces funding volatility, strengthening bank stability (Han & Melecky, 2013). Likewise, Morgan and Pontines (2014) argue that Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) lending reduces non-performing loans. Yet, Pham and Doan (2020) observed only marginal stability benefits from financial inclusion in Asian economies with weak banking oversight. Khan (2011) identifies mechanisms linking inclusion and stability: diversified financial systems, stronger retail deposit bases, and improved monetary policy transmission. Nonetheless, Sahay et al. (2015) warn that in weakly regulated environments, expanded credit may erode bank capital buffers, heightening systemic risks.

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, Neaime and Gaysset (2018) confirmed a positive relationship between financial inclusion and deposit growth stability. Similarly, Siddik, Sun, Kabiraj, Shanmugan, and Yanjuan (2018) found that SME-focused inclusion improves banking stability. However, these findings are context-specific. The World Bank (2012) emphasises that financial inclusion generally supports stability in developing economies, though Ardic, Heimann, and Mylenko (2013) and Sahay et al. (2015) stress the critical role of effective regulation. Zimbabwe’s unique economic and regulatory conditions, therefore, warrant further country-specific research.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Research Design

The study adopted a quantitative research design and employed an econometric modelling approach to systematically collect, analyse, and interpret numerical data for explaining relationships among economic variables (Creswell, 2003; Creswell, 2011). Specifically, the study utilised the Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) estimation technique developed by Phillips and Hansen (1990). The choice of FMOLS over conventional Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Vector Error Correction Models (VECM) was based on its robustness in estimating long-run cointegrating relationships among non-stationary time series variables. Unlike standard OLS, FMOLS corrects for both serial correlation and endogeneity that typically arise in cointegrated systems, thereby producing unbiased and efficient estimators (Phillips & Hansen, 1990; Hansen, 1992). Additionally, while VECM can capture short-run dynamics, FMOLS is more suitable when the research objective focuses on long-run equilibrium relationships among variables (Pedroni, 2000). The FMOLS technique was also chosen because it is well-suited for small sample sizes and effectively corrects for serial correlation and endogeneity bias that often arise in cointegrated time series, ensuring robust long-run estimates (Phillips & Hansen, 1990). The model specified economic development (ED) proxied by real GDP per capita as the dependent variable, while financial inclusion (FI), domestic credit to the private sector (DCPS), and broad money supply (M2) served as key explanatory variables. Inflation (INF) and foreign direct investment (FDI) were included as control variables to capture macroeconomic influences, with all variables expressed in their natural logarithmic forms to stabilise variance and interpret coefficients as elasticities. The FMOLS approach was thus appropriate for achieving the study’s objective of examining the long-run relationship between financial inclusion and economic development in Zimbabwe.

Model Specification

The time series data will be estimated and analysed using the Cointegration technique fully modified ordinary least squares method.

Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability Model

The model measures the impact of financial inclusion on bank system stability. Financial inclusion is measured by depositors with commercial banks (per 1,000 adults while bank Z-score proxies financial stability.

LBS𝑖𝑡=𝛼+𝛽1LFI𝑖𝑡+𝛽2LGDP𝑖𝑡+𝛽3LDC𝑖𝑡+𝛽4LBM𝑖𝑡+𝜀𝑖𝑡

α the constant term;

β the coefficient of the function;

𝜀𝑖𝑡 the disturbance or error term (assumed to have zero mean and independent across the time period).

Variable Definitions and Proxies:

LBS Bank system stability, proxied by the bank Z-score, which measures the probability of default and the overall soundness of the banking system.

LFI Financial inclusion, measured by the number of depositors with commercial banks per 1,000 adults, indicating the extent of access to and use of formal financial services.

LGDP Gross Domestic Product (GDP), included as a control variable to account for the level of economic growth and overall macroeconomic performance.

LDC Domestic credit to the private sector, representing credit availability and financial sector depth, which can influence both inclusion and stability.

LBM Broad money (M2), serving as a proxy for financial sector liquidity and monetary depth in the economy.

All variables are expressed in natural logarithmic form (log-linear specification) to stabilise variance, reduce heteroscedasticity, and interpret the coefficients as elasticities.

Secondary Data Sources

Secondary data was used, as it is cost-effective and pre-processed. Data was sourced from the World Bank database, IMF, Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe reports, POTRAZ, and AFDB. The World Bank database was preferred for its reliability and direct data collection, minimising errors and biases. Other relevant journals on financial inclusion and stability were also consulted.

Data Presentation, Analysis, and Interpretation

The findings were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics included trend analysis over the years for the variables under study. Inferential statistical techniques, such as Pearson’s correlation and regression analysis, were used to establish causal relationships between digital finance and financial inclusion. Time series data for the models were analysed using EViews 12. Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) and cointegration techniques were employed. Regression analysis assessed model fitness using the R-Square value and regression coefficients. Data were presented using tables and figures.

Diagnostic Tests

To ensure that estimated variables were Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUE), several diagnostic tests were conducted. The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test confirmed stationarity, rejecting the null hypothesis of a unit root if the p-value was below 0.05. Multicollinearity was assessed through pairwise correlations, with coefficients above 0.8 indicating concern. The Jarque-Bera test confirmed normality of residuals, while the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey (BPG) test confirmed homoscedasticity if the p-value exceeded 0.05. The Breusch-Godfrey LM test assessed autocorrelation, with p-values above 0.05 suggesting no autocorrelation. Cointegration tests confirmed a long-run relationship, ensuring model robustness and reliability.

Descriptive Statistics

Financial Stability and Financial Inclusion

The descriptive statistics in Table 1 provide an overview of the key variables: bank system stability (LBS), financial inclusion (LFI), domestic credit (LDC), broad money (LBM), and GDP (LGDP). These include measures such as the mean, median, maximum, minimum, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and normality tests (Jarque-Bera).

The descriptive statistics indicate that the data exhibit normality, low variability, and minimal skewness, confirming their suitability for econometric analysis. The mean and median values for LBS (1.708 and 1.637) and LDC (2.888 and 2.908) are closely aligned, indicating symmetric distributions. Standard deviations for LBS (0.173) and LBM (0.543) reflect low variability around the mean. However, LBM shows non-normality, with a Jarque-Bera statistic of 15.280 (p = 0.00048), suggesting a need for robustness checks or data transformation to mitigate bias. Skewness values for LBS (0.765) and LDC (0.406) indicate slight right-tail concentration, while LFI (-0.530) and LGDP (-0.352) exhibit left-tail skewness, reflecting a reasonably balanced dataset. The range for LFI (maximum: 3.292, minimum: -1.931) and LGDP (maximum: 3.292, minimum: -2.244) demonstrates sufficient variability for meaningful regression analysis.

Diagnostic Tests

Prior to regression, diagnostic tests were conducted, including Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit root tests, co-integration tests, autocorrelation, and multicollinearity assessments.

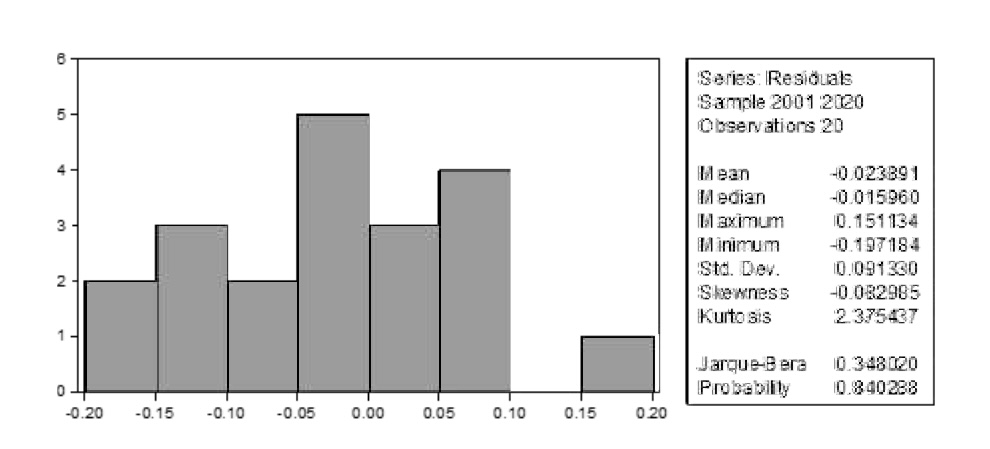

Normality Test

Residual analysis shows the model meets normality assumptions. The residual mean (0.023891) and median (0.015360) are close to zero, with low variability (standard deviation: 0.091330). Skewness (-0.083985) and kurtosis (2.745437) values indicate near-symmetry and a distribution close to normal. The Jarque-Bera statistic (0.348020, p = 0.840288) confirms normality, validating the model’s specification and reliability. Residuals range between -0.191184 and 0.151134, supporting accurate, unbiased predictions.

Source: Author's computations from Eviews version 12, 2025

Unit Root Test and Stationarity Analysis

This study employed the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test to assess the stationarity of variables, addressing the null hypothesis of a unit root against the alternative of stationarity. As emphasised by Gujarati (2004), the null hypothesis is rejected if the absolute ADF statistic exceeds critical values at 1%, 5%, or 10% significance levels, confirming stationarity.

The results in Table 2 demonstrate mixed orders of integration across the variables. For LBS, the ADF statistic of -4.2717 exceeds the 1%, 5%, and 10% critical values, with a p-value of 0.0040, indicating stationarity after first differencing (I(1)). Similarly, LGDP achieves stationarity at first difference (ADF = -2.7644; p = 0.0832), though with marginal significance, suggesting weak evidence of stationarity. Variables such as LFI, LBM, and LDC are non-stationary at both levels and first difference but become stationary at the second difference (I(2)). This is supported by significant ADF statistics: -3.9633 (LFI), -4.8418 (LBM), and -4.7570 (LDC), all exceeding critical thresholds with p-values below 0.01. The residuals (RESID) are stationary after first differencing (ADF = -6.2729; p = 0.0003), validating the regression model’s stability and justifying further econometric procedures. Overall, the stationarity structure indicates that LBS, LGDP, and RESID are integrated of order one (I(1)), while LFI, LBM, and LDC are integrated of order two (I(2)). This mix of integration orders necessitates appropriate modelling techniques, such as cointegration analysis, to avoid spurious regressions and ensure robust, reliable inference on the relationships between financial inclusion, stability, and economic growth in Zimbabwe.

Cointegration Test and Long-Run Relationship Analysis

The cointegration test was conducted to determine whether a stable long-run relationship exists among the model variables, minimising the risk of spurious regression results. Given the mixed stationarity levels identified by the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test, cointegration analysis is essential to assess whether the variables move together over time despite short-term fluctuations. This study applied the Engle-Granger Residual-Based Cointegration Test, following the approach of Engle and Granger (1987) and Gujarati (2004). The test examines the stationarity of residuals from the long-run regression. If residuals are stationary, it implies that a long-run equilibrium relationship exists, even if individual variables are non-stationary.

The results indicate an ADF statistic for the residuals of -6.272937, exceeding critical values at the 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, with a p-value below 0.05. This provides strong evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration, confirming residual stationarity at level I(0). The findings demonstrate a significant long-run equilibrium relationship between financial inclusion, banking system stability, GDP, and banking models. This suggests that despite short-term instability, these variables are interconnected over time, reinforcing the role of financial inclusion in promoting sustainable economic development and banking sector resilience in Zimbabwe.

Autocorrelation Test

To test for autocorrelation, the Durbin-Watson (DW) statistic was used. The results show DW 1.845240, which is greater than 1.5, indicating no serial autocorrelation in the residuals, as supported by the p-values above 0.05.

Multi-collinearity Test

Regarding multi-collinearity, the correlation coefficients for the independent variables are generally below 0.8, except for RT and GDP. This suggests that multi-collinearity is not severe, and there is no significant linear relationship among the explanatory variables, allowing clear identification of each variable's influence on the dependent variable.

To this end, the researcher adopted the do-nothing school of thought as expressed by Blanchard (1967) in Gujarati (2004). This means that there is no linear relationship among the explanatory variables, and it is easy to establish the influence of each one variable on the dependent variable, financial inclusion, separately. The strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables were measured by performing a correlation matrix. It can be deduced from Table 3 that there is a moderate negative correlation between bank system stability (LBS) and both financial inclusion (LFI) (-0.592) and gross domestic product (LGDP) (-0.532). This indicates that as financial inclusion and economic activity increase, banking system stability tends to decline moderately. In contrast, domestic credit (LDC) and broad money (LBM) exhibit negligible positive correlations with bank stability, reflected by coefficients of +0.0415 and +0.0783, respectively. Moreover, there exists a strong positive correlation between financial inclusion (LFI) and GDP (LGDP) (0.986), suggesting a high degree of association between these two variables. This high correlation points to potential multicollinearity, which warrants the use of robust estimation techniques such as Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS) to obtain consistent and unbiased estimates.

Regarding multicollinearity, the correlation coefficients for the independent variables are generally below 0.8, except for LFI and LGDP. This suggests that multicollinearity is not severe overall, and there is no significant linear dependency among most explanatory variables. Thus, the influence of each variable on the dependent variable can be distinctly identified.

Heteroskedasticity

The Bruesch-Pagan Godfrey Test probability value of 0.0321 for the model is less than the significance level of 0.05. This therefore implies that the errors are homoscedastic and that we may fail to reject the null hypothesis that the errors are homoscedastic.

Regression Results

The regression results from the Fully Modified Least Squares (FMOLS) method show that the variables LBM, LFI, LDC, and LGDP have significant relationships with the dependent variable. LBM has a positive effect, with a coefficient of 0.102876, indicating that for each unit increase in LBM, the dependent variable increases by approximately 0.103 units.

On the other hand, LFI and LDC exhibit negative relationships, with coefficients of -0.267849 and -0.220615, respectively, suggesting that higher values of LFI and LDC lead to decreases in the dependent variable. LGDP, with a positive coefficient of 0.195355, shows that as LGDP increases, the dependent variable also increases. The constant term (C) is 2.162129, meaning that when all independent variables are zero, the dependent variable equals this value.

The significance of the coefficients is confirmed by the t-statistics and p-values, with LFI, LDC, and LGDP being highly significant at the 1% level, while LBM is significant at the 10% level. The model explains 61.85% of the variation in the dependent variable (R-squared), with an adjusted R-squared of 51.67%, indicating a relatively good fit. The standard error of regression (0.106426) suggests a reasonable level of accuracy in the predictions, and the long-run variance value of 0.004586 reflects the variability explained by the model over time.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

Financial Inclusion, Banking System Stability, and Economic Development in Zimbabwe

This study highlights the complex relationship between financial inclusion, banking system stability, and economic development in Zimbabwe. Regression results reveal that financial inclusion (LFI), banking system stability (LDC), and economic growth (LGDP) significantly influence financial system effectiveness, with implications for livelihoods and economic stability. The negative coefficient for LFI (-0.267849) suggests that financial inclusion may destabilise Zimbabwe’s fragile financial system. This supports Minsky’s (1986) Financial Instability Hypothesis, which posits that while access to finance can promote growth, poorly managed inclusion increases systemic risk. Expanding access without adequate regulation may lead to defaults, over-indebtedness, and financial volatility. Zimbabwe’s banking sector already faces inflation, liquidity constraints, and weak risk management, making rapid inclusion potentially destabilising.

Similarly, the negative coefficient for LDC (-0.220615) reflects the importance of a stable banking sector. According to Diamond and Dybvig’s (1983) Theory of Bank Runs, confidence in banks is critical for economic stability. High non-performing loans (NPLs), liquidity shortages, and financial fragility undermine both inclusion and resilience. Tressel and Verdier (2008) emphasise that banking stability is a prerequisite for effective inclusion, a finding consistent with Zimbabwe's experience. Conversely, the positive coefficient for LGDP (0.195355) aligns with Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Levine (2007) and Romer’s (1990) Endogenous Growth Theory, which suggests that economic growth drives financial development. Zimbabwe’s initiatives promoting mobile money and digital finance (World Bank, 2023) have improved financial access, though macroeconomic instability continues to limit broader financial sector development.

The positive coefficient for LBM (0.102876) highlights the importance of robust banking models. Nguyen and Dang (2022) argue that strong risk management and capital adequacy enable banks to absorb shocks while expanding services. Strengthening banking operations and regulatory oversight is essential for achieving sustainable inclusion without compromising system stability.

Schumpeter’s (1911) theory of creative destruction suggests that while financial innovation promotes growth, unregulated expansion can destabilise institutions. Zimbabwe’s mobile money growth has increased financial activity, but vulnerabilities persist due to inflation, currency volatility, and regulatory gaps ( Gup, 2004). The Financial Intermediation Theory (Bagehot, 1873) explains the role of banks in linking savers and borrowers to promote growth and inclusion. Yet, Zimbabwe’s banks face liquidity constraints, poor credit risk management, and growing competition from mobile money, exacerbating systemic weaknesses unless regulatory integration improves.

Empirical studies echo these findings. Hannig and Jansen (2010) caution that rapid inclusion in weak banking environments can destabilise the sector, a dynamic visible in Zimbabwe. Beck et al (2007) similarly stress that financial system stability underpins successful inclusion. Despite mobile money expansion, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ, 2023) reports persistent sectoral instability, including high NPLs and liquidity shortages. Dube (2023) emphasises the need for regulatory reforms, financial literacy, and improved bank capitalisation to balance inclusion with financial stability. Mavaza (2023) adds that ensuring banks can absorb growing demand for services is critical to supporting livelihoods and sector resilience.

The negative inclusion-stability relationship aligns with World Bank (2012) and Sahay et al. (2015), who found that in low-income countries with weak financial systems, increased credit access can undermine stability. Zimbabwe’s fragile banking sector, with liquidity shortages and high NPLs, reflects this risk. While some global studies report positive links between inclusion and stability (Jungo, Madaleno, and Botelho, 2022; Al-Smadi, 2018; Morgan and Pontines, 2014), their focus on more stable economies limits relevance to Zimbabwe. The World Bank (2012) and Sahay et al. (2015) emphasise that weak banking oversight amplifies the risks of expanded financial access. In conclusion, this study underscores the dual role of financial inclusion in promoting growth and livelihoods while posing stability risks in fragile economies like Zimbabwe. Strengthening regulation, improving risk management, and enhancing financial literacy are critical to ensuring that inclusion supports sustainable economic development.

CONCLUSION

This study reveals a negative and statistically significant relationship between financial inclusion and financial stability in Zimbabwe, consistent with Minsky’s (1986) Financial Instability Hypothesis and Diamond and Dybvig’s (1983) Theory of Bank Runs. While financial inclusion promotes economic growth, its rapid expansion in a fragile banking environment increases systemic risks. The results show that financial inclusion and domestic credit negatively affect banking stability, while GDP and financial sector size positively influence stability. Poorly regulated microfinance institutions and weak credit assessments further amplify vulnerabilities. Strengthening regulatory frameworks, enhancing financial literacy, and improving bank capitalisation are essential to ensure that financial inclusion supports, rather than undermines, long-term economic stability.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Government and Regulators

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe and relevant ministries should enhance cybersecurity to protect digital financial services and prevent fraud, building public confidence. Infrastructure development in rural areas, including roads and electricity, is essential, with incentives for private investment in ICT. A supportive legal framework should accommodate financial technology innovations without regulatory barriers.

Financial Institutions and Mobile Network Operators (MNOs)

Banks and MNOs should offer small loans via mobile banking to financially excluded individuals and support group savings schemes like burial societies with multi-signatory accounts. Expanding branchless banking—via mobile and agent banking—will cut costs and improve access.

Central Bank

To restore trust, the central bank must address high bank charges, low savings returns, and rigid account-opening procedures while ensuring financial stability.

Banking Sector

Banks should invest in financial literacy to educate underserved populations and collaborate on shared infrastructure like ATMs and mobile banking platforms. A Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) can reduce costs and enhance service delivery.

Private Sector

Banks and MNOs should conduct educational campaigns on digital financial products, boosting financial inclusion and sector growth, especially in rural areas.

REFERENCES

Adrian, T., & Shin, H. S. (2010). Liquidity and leverage. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19(3), 418–437.

Allen, F., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Peria, M. M. (2012). Foundations of financial inclusion. Policy Research Working Paper, 6290.

Allen, F., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Pería, M. S. M. (2014). The foundations of financial inclusion: Understanding ownership and use of formal accounts. Policy Research Working Paper No. 6290. World Bank.

Allen, F., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Peria, M. S. M. (2016). The foundations of financial inclusion: Understanding ownership and use of formal accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 27, 1-30.

Al-Smadi, M. (2018). Financial inclusion and stability in Jordan: An FMOLS approach. International Journal of Financial Studies, 6(3), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs6030071

Al-Smadi, M. O. (2018). The role of financial inclusion in financial stability: Lesson from Jordan. Banks and Bank Systems, 13(4), 31-39. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.13(4).2018.03

Amatus, H., & Alireza, N. (2015). Financial inclusion and financial stability in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). International journal of social sciences, 36(1), 2305-4557.

Ardic, O. P., Heimann, M., & Mylenko, N. (2013). Access to financial services and stability: A cross-country analysis. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Atkinson, A., & Messy, F. (2013). Promoting financial inclusion through financial education: OECD/INFE evidence, policies and practice. OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 34. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k3xz6m88smp-en

Bagehot, W. (1873). Lombard Street: A description of the money market. London, England: Henry S. King and Co.

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2019). The stability of the financial system: Risks and regulation.

Barugahara, F. (2021). Financial inclusion in Zimbabwe: Determinants, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of African Finance and Economic Development, 8(2), 45-61.

Barugahara, I. (2021). Determinants of financial inclusion in Zimbabwe: Evidence from micro-data. African Journal of Economics and Finance, 5(2), 34–52.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2007). Finance, inequality, and poverty: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 27-49.

Bhattacharya, S., & Thakor, A. V. (1993). Contemporary banking theory. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 3(1), 2-50. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfin.1993.1002

Brunnermeier, M. K. (2009). Deciphering the liquidity and credit crunch 2007–2008. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(1), 77-100. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.23.1.77

Camara, N., Peña, X., & Tuesta, D. (2014). Financial inclusion and education in Peru: Evidence from household surveys. Central Bank of Peru Working Paper.

Camara, N., Peña, X., & Tuesta, D. (2014). Factors that matter for financial inclusion: Evidence from Peru. BBVA Research Working Paper No. 14/09. https://www.bbvaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/WP14-09_Factors-that-matter-for-financial-inclusion

Chivasa, W., & Simbanegavi, W. (2016). Determinants of financial inclusion in Zimbabwe: A focus on rural areas. African Journal of Economic Review, 4(2), 1–20.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2 ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2 ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Danjuma, I. (2018). Financial inclusion and banking stability: Evidence from emerging markets. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 8(5), 1–12.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). The Global Findex Database 2014: Measuring financial inclusion around the world (Policy Research Working Paper No. 7255). World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-7255

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Singer, D. (2017). Financial inclusion and inclusive growth: A review of recent empirical evidence (Policy Research Working Paper No. 8040). World Bank.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global Findex database 2017.

Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, Saniya Ansar, and Jake Hess. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the FinTech Revolution. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1259-0

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank Publications.

Diamond, D. W., & Dybvig, P. H. (1983). Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. Journal of Political Economy, 9(13), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1086/261155

Dube, S. (2023). Digital financial inclusion and economic development in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence and policy implications. African Journal of Economic Policy, 30(2), 45-62.

Dube, T. (2023). Financial stability challenges and regulatory reforms in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Economic Review, 18(3), 45–63.

Engle, R. F., & Granger, C. W. J. (1987). Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica, 55(2), 251–276. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913236

European Central Bank. (2019). Financial Stability Review.

Greenwood, J., & Jovanovic, B. (1990). Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 1076–1107. https://doi.org/10.1086/261720

GSMA. (2020). Mobile money and financial inclusion: Emerging trends in developing countries. GSMA: London.

Gujarati, D. N. (2004). Basic econometrics (4 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Gup, B. E. (2004). Banking and financial stability. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Gwalani, H., & Parkhi, S. (2014). Barriers to financial inclusion in India: Evidence from rural households. Indian Journal of Finance, 8(5), 25–38.

Gwalani, H., & Parkhi, S. (2014). Financial inclusion – Building a success model in the Indian context. Procedia -Social and Behavioural Sciences, 133, 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.203

Han, R., & Melecky, M. (2013). Financial inclusion for financial stability: Access to bank deposits and systemic risk. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6371. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-6371

Han, R., & Melecky, M. (2013). Financial inclusion for financial stability: Access to bank deposits and the growth of deposits in the global financial crisis. Policy Research Working Paper No. 6577. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-6577

Hannig, A., & Jansen, S. (2010). Financial inclusion and financial stability: Current policy issues. Asian Development Bank Working Paper Series.

Hansen, B. E. (1992). Consistent covariance matrix estimation for dependent heterogeneous processes. Econometrica, 60(4), 967–972. https://doi.org/10.2307/2951594

Honohan, P. (2008). Cross-country variation in household access to financial services. Journal of Banking & Finance, 32(11), 2493–2500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2008.05.004

IMF (International Monetary Fund). (2015). Financial inclusion: Policy and regulatory considerations. Washington, DC: IMF.

Indonesia Ministry of Finance. (2014). Financial inclusion strategy: Empowering Indonesia’s unbanked population. Government of Indonesia.

Institute for Inclusive Social & Public Policy Research. (2023). Enhancing financial inclusion in underserved regions: Pathways to inclusive economic development. Institute for Inclusive Social & Public Policy Research.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2015). Financial inclusion: Can it meet multiple macroeconomic goals? IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/15/17. International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513562647.006

Jungo, J., Mara, M., & Anabela, B. (2022). Effect of financial inclusion and competitiveness on financial stability: Why financial regulation matters in developing countries. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 45(5), 780–797.

Jungo, L., Madaleno, M., & Botelho, A. (2022). Financial inclusion and banking stability in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Journal of African and Latin American Finance, 10(1), 45–63.

Kabakova, I., & Plaksenkov, E. (2018). Determinants of financial inclusion in developing countries. Emerging Markets Finance & Trade, 54(10), 2241–2256. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2017.1416341

Kabakova, O., & Plaksenkov, E. (2018). Analysis of factors affecting financial inclusion: Ecosystem view. Journal of Business Research, 89, 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.066

Khan, H. R. (2011). Financial inclusion and financial stability: Are they two sides of the same coin? Address at BANCON 2011, November 4. Chennai, India: Reserve Bank of India.

Khan, H. R. (2011). Financial inclusion versus stability: Evidence from developing economies. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 3(2), 50–61.

Mandić, A., Marković, B., & Žigo, I. R. (2025). Risks of the use of FinTech in the financial inclusion of the population: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050250

Mavaza, T. (2023). Banking system resilience and inclusive finance in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Finance and Economics, 11(1), 77–95.

Mhlanga, D. (2021). Factors that matter for financial inclusion: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa (The Zimbabwe case). Sustainability, 10(6), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su1006212

Mhlanga, M. (2020a). Digital financial inclusion in Zimbabwe: Trends and challenges. Journal of African Development Studies, 12(1), 45–63.

Microfinance Gateway. (2017). Expanding financial access: Key drivers and innovations. Washington, DC: CGAP.

Minsky, H. P. (1986). Stabilising an unstable economy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Morgan, P., & Pontines, V. (2014). Financial stability and financial inclusion: Evidence from ASEAN economies. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 6(2), 120–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFEP-03-2013-0011

Mutale, J., & Nyathi, L. D. (2024). An ARDL approach to evaluating illicit financial flows and economic development in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation, 11(9), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.51244/ijrsi.2024.1109022

Mutale, J., & Shumba, D. (2024). The impact of digital finance on financial inclusion in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Inclusive Societies, 4(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.59186/SI.QRTY5NM3

Neaime, S., & Gaysset, I. (2018). Financial inclusion and stability in MENA: Evidence from poverty and inequality. Finance Research Letters, 24, 230-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2017.09.007

Nguyen, Q. K., & Dang, V. C. (2022). The impact of risk governance structure on bank risk management effectiveness: Evidence from ASEAN countries. Heliyon, 8(10).

Novotny-Farkas, Z. (2016). The interaction of the IFRS 9 expected loss approach with supervisory rules and implications for financial stability. Accounting in Europe, 13(2), 197–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2016.1210180

Patwardhan, P. (2018). Financial inclusion, resilience and economic growth. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 10(4), 1–12.

Pedroni, P. (2000). Fully modified OLS for heterogeneous cointegrated panels. Advances in Econometrics, 15, 93–130.

Pham, H., & Doan, T. P. L. (2020). The impact of financial inclusion on financial stability in Asian countries. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(6), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no6.047

Phillips, P. C. B., & Hansen, B. E. (1990). Statistical inference in instrumental variables regression with I(1) processes. Review of Economic Studies, 57(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297545

Prasad, E. S. (2010). Financial sector regulation and reforms in emerging markets: An overview.

Ramakrishna, G., & Trivedi, J. (2018). Digital banking and financial inclusion: An empirical study in India. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 7(2), 77–88.

Ramakrishna, S., & Trivedi, P. (2018). Technology and financial inclusion in emerging economies. Journal of Financial Innovation, 4(2), 25–39.

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ). (2020). National Financial Inclusion Strategy. Harare: RBZ.

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ). (2022). Financial inclusion and banking stability report. Harare: RBZ.

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ). (2022). Monetary policy statement. Harare: RBZ.

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ). (2023). Financial sector stability update. Harare: RBZ .

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. (2020). National Financial Inclusion P-Strategy Progress Report 2016–2020. Harare: Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe.

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. (2022). National financial inclusion strategy II (2022–2026). Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), S71–S102. https://doi.org/10.1086/261725

Sahay, R., Čihák, M., N’Diaye, P., Barajas, A., Mitra, S., Kyobe, A., Mooi, Y. N., & Yousefi, S. R. (2015). Financial inclusion: Can it meet multiple macroeconomic goals? IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/15/17. International Monetary Fund.

Sarma, M. (2008). Index of Financial Inclusion (ICRIER Working Paper No. 215). Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1911). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Harvard University Press.

Siddik, M. A. & Kabiraj, S. (2018). “Does Financial Inclusion Induce Financial Stability? Evidence from Cross-country Analysis. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 12(1), 34-46. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v12i1.3

Tressel, T., & Verdier, T. (2008). Financial globalization and the governance of domestic financial intermediaries. Journal of Economic Theory, 133(1), 79–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jet.2005.12.007

Tshuma, P., Tshuma, N., Mpofu, S., & Sango, E. (2023). An analysis of the impact of digital financial inclusion on financial stability. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 7(4), 994–1006. https://doi.org/10.47772/IJRISS

Ulwodi, D. W., & Muriu, P. W. (2017). Barriers of financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 8(14).

United Nations (UN). (2021). Financial inclusion for sustainable development: Building inclusive financial systems. New York, NY: United Nations.

United Nations. (2018). Building inclusive and resilient societies through financial inclusion. United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF).

United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF). (2022). Financial inclusion and the Sustainable Development Goals. UNCDF.

United Nations Capital Development Fund. (2022). Advancing sustainable development through financial inclusion: UNCDF’s role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). United Nations Capital Development Fund.

United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Advocate for Inclusive Finance for Development (UNSGSA). (2022). Annual report 2022: Expanding access, amplifying impact.

World Bank. (2012). Financial inclusion strategies reference framework. World Bank Publications. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/702011468152092070/financial-inclusion-strategies-reference-framework

World Bank. (2015). World Development Report 2015: Mind, society, and behavior. World Bank Publications. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0342-9

World Bank. (2020). The global financial development report 2020: Bank regulation and supervision: a decade after the global financial crisis. World Bank Publications. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1451-7

World Bank. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank Publications. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-3

World Bank. (2023). Zimbabwe digital financial services and inclusion report 2023. World Bank.

Yoshino, N., & Morgan, P. (2016). Overview of financial inclusion, regulation, and education. In N. Yoshino & P. Morgan (Eds.), Financial inclusion, regulation, and education. 1-20.