BACKGROUND AND STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) launched the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), aiming to eradicate poverty, protect the environment, and achieve equitable well-being globally (UN, 2016). As Africa embarks on this ambitious journey, the role of both women and men in leadership has become central to the discourse on socio-political progress. The intersection of gender, culture, and leadership dynamics raises critical questions about how these factors shape political landscapes at national and continental levels, especially in regions like Western Kenya. This paper examines the multifaceted ways in which women and men from Western Kenya influence politics within Kenya and beyond, with a particular focus on how gender roles and cultural frameworks shape leadership in this context.

Historically, leadership in African societies, including those in Western Kenya, has been predominantly viewed through a male lens, driven by patriarchal structures rooted in traditional, cultural, and social norms (Ogbodo et al., 2022). Communities like the Luhya and Kisii in Western Kenya have long adhered to patriarchal hierarchies that position men in leadership roles. However, with increasing global advocacy for gender equality and inclusivity, there has been a notable shift toward recognising the leadership capacities of women. In Kenya, this shift is manifesting through policies and initiatives aimed at empowering both women and men in political and economic spheres, resulting in new models and structures of leadership that challenge established cultural norms. This transformation is anchored in the Constitution of Kenya (2010), which introduced the two-thirds gender rule (Articles 27[8] and 81[b]) to promote gender parity in elective and appointive positions (Republic of Kenya, 2010). The establishment of the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC) and other gender-responsive institutions has advanced gender mainstreaming within governance and policy frameworks (NGEC, 2023).

Government-led programs such as the Women Enterprise Fund (WEF) and Uwezo Fund have enhanced economic participation among women and youth, creating new pathways for inclusive leadership and entrepreneurship (Ministry of Public Service, Gender and Affirmative Action, 2022). Empirical evidence further supports this transformation: women now occupy 23% of National Assembly seats and 31% of Senate seats, up from 9% in 2013 (UN Women, 2023), while seven female governors were elected in 2022 compared to none in 2013 (IEBC, 2022).

At the county level, initiatives such as the Council of Women Governors have institutionalised mentorship and gender- responsive budgeting (Council of Governors, 2022). Moreover, studies demonstrate growing acceptance of women’s leadership and participation in governance. For instance, Mutinda, Magutu, and Tshiyoyo (2025) show that gender-sensitive economic policies and empowerment programs have significantly improved women’s agency and political engagement in urban and rural Kenya. Similarly, according to Minja et al. (2025), deliberate capacity-building programs and affirmative action policies have reshaped leadership structures, promoting shared decision-making and enhanced inclusivity of both men and women in governance processes.

The discourse on gender and leadership in Africa has gained significant momentum in recent years, spurred by international frameworks such as the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the SDGs, both of which call for gender parity in leadership roles (African Union, 2020). Western Kenya offers a compelling case study for exploring these dynamics, as both women and men from this region increasingly rise to positions of influence within local, national, and continental political arenas. However, as Mikell (1997) argues, the intersection of gender and culture in African political and social life remains deeply complex cultural norms, social organiszation (such as dual-sex systems), and traditional values continue to influence leadership opportunities, especially for women, within frameworks of power, survival, and social belonging.

Leadership, particularly in African contexts, is often defined by cultural and social structures. In traditional Western Kenyan communities, such as the Luhya and Kisii, leadership was historically determined by factors like age, clan affiliations, and wealth, often excluding women from formal political leadership. Obara and Nyanchoga (2025) show that among the Abagusii, leadership has historically been structured around clan affiliations and elder councils, which have marginalised certain clans and constrained equitable political representation. As described by Gumo (2018), Luhya communities traditionally organised socially and politically through clan-based governance led by elders, with decisions on conflict, land, and resource management largely made by these elder councils rather than centralised authority. Today, both women and men leaders from Western Kenya face the dual challenge of negotiating deeply ingrained cultural norms while aligning with national and continental political agendas that emphasise gender inclusivity. In a region where cultural identity is as important as political affiliations, leadership styles that embrace cultural awareness are emerging as effective tools for bridging the gap between tradition and modernity. While traditional values remain influential, leaders like Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi and Martha Karua also reflect a modern political vision, blending their cultural identity with progressive leadership as documented in their public careers (Pulselive, 2025; Kenya Yearbook, 2022).

Cultural norms, economic expectations, and local political traditions continue to shape leadership dynamics in Kenya. For instance, Nzomo (2011) shows that patriarchal values remain deeply embedded in governance structures, while studies in counties such as Kakamega reveal how ethnic and clan affiliations influence women’s access to leadership. Furthermore, the Ubuntu philosophical tradition underscores how communal values can both support and limit women’s political participation in modern Kenya (Aringo & Odongo, 2025).

The discourse on leadership in Africa has historically been dominated by Western paradigms that often marginalise indigenous systems (Kuada, 2010). Recent scholarship, however, highlights that African cultural frameworks, encompassing both men’s and women’s leadership traditions, provide alternative governance models that challenge patriarchal power and foster social equity (Nkomo & Ngambi, 2009). This study positions both women and men from Western Kenya as transformative agents redefining leadership and political participation within a context still marked by deep-rooted cultural expectations.

At the heart of this transformation lies a persistent challenge: while constitutional reforms and global advocacy have expanded opportunities for women, patriarchal ideologies and cultural constructs continue to limit their participation in formal political leadership. In communities such as the Luhya and Kisii, women who exert influence in domestic and civic spheres often face systemic barriers including exclusion from party politics, gender stereotyping, and limited access to economic and educational resources. These structural inequalities do not only marginalise women but also restrict men’s potential to engage as champions of gender-equitable governance.

Across the continent, countries such as Rwanda, Ethiopia, and South Africa demonstrate how gender-inclusive leadership can advance national unity, peacebuilding, and sustainable development (Sow, 2019). Kenya’s own experience, though promising, remains uneven. Persistent socio-cultural biases and institutional barriers continue to frustrate the realisation of the two-thirds gender rule (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2021). Yet, the growing visibility of both women and men leaders from Western Kenya, ranging from grassroots mobilisers to global figures like Prof. Anyang’ Nyong’o and Lupita Nyong’o, illustrates the region’s evolving contribution to national and continental leadership narratives (Mwaniki, 2017).

In essence, the leadership transformation unfolding in Western Kenya represents a negotiation between cultural continuity and social progress. While patriarchy remains deeply entrenched, increasing advocacy, education, and policy interventions are reshaping leadership to embrace both genders as partners in governance. This study seeks to unpack these dynamics, examining how cultural and gendered experiences shape leadership trajectories in Western Kenya and how such transformations can inform inclusive political development across Africa.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Globally, gender continues to shape leadership trajectories, as cultural and social norms influence who is perceived as capable or legitimate to lead. Across diverse societies, men have historically dominated political, corporate, and community leadership spaces, while women have often been relegated to the margins of power (UN Women, 2025; ALIGN Platform, 2019). This disparity is underpinned by deeply embedded patriarchal ideologies that privilege male authority and constrain women’s access to decision-making opportunities.

Nevertheless, global frameworks such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and Sustainable Development Goal 5 have stimulated progress toward gender equality. They provide both normative and strategic foundations for states to promote inclusive leadership. Within Africa, these commitments have inspired countries like Kenya to institutionalise affirmative action and create gender-responsive policy mechanisms. Such global–local linkages affirm that gender equality in leadership is not merely a legal issue but a transformative social process that requires dismantling structural inequalities and redefining cultural meanings of power (Adichie, 2017; UN Women, 2023).

In most African contexts, cultural traditions and patriarchal systems have historically defined leadership as a male prerogative (Tripp et al., 2009). Leadership is often embedded within lineage, age, and patriarchal authority structures, which symbolically associate leadership with masculinity. These traditions remain influential in Kenya, particularly in rural regions such as Western Kenya, where women’s leadership roles have often been restricted to informal or domestic spheres. Yet, Kenyan society has undergone significant cultural transformation due to education, religious change, urbanisation, and globalization all of which have opened new spaces for women’s agency.

Women’s participation in church leadership, self-help groups, savings cooperatives, and county assemblies reflects this gradual redefinition of authority. While men still dominate formal political offices, women increasingly exercise leadership through socially acceptable and community-based platforms. As observed by Kamau (2010), these emergent roles are reshaping the moral and cultural narratives surrounding leadership, allowing women to “lead from within” their cultural systems rather than outside them. This indicates that gendered leadership in Kenya is best understood as an evolving negotiation between cultural expectations and changing socio-political realities.

Kenya’s 2010 Constitution introduced the two- thirds gender rule, mandating that no more than two-thirds of elective or appointive bodies should be of the same gender. This legal framework, although inconsistently implemented, represents a major policy step toward women’s inclusion in governance (Tripp et al., 2009). The Kenyan experience draws from successful models in Rwanda and South Africa, where gender quotas have dramatically improved women’s political representation. At the grassroots level, women’s networks such as the Western Kenya Women’s Leadership Network (WKWLN) have taken a culturally sensitive approach to empowerment by combining mentorship, economic support, and civic education. These initiatives translate national policy into everyday practice by cultivating leadership competencies within community settings. Theoretically, such approaches align with empowerment and social change paradigms that emphasise participation, collective action, and the transformation of everyday gender relations (Cornwall & Rivas, 2015).

Despite significant legislative progress, Kenyan women continue to face persistent obstacles, including cultural resistance, economic marginalisation, and gender-based violence (Krook & Restrepo Sanín, 2020). Patriarchal political networks, limited access to campaign financing, and stereotypes portraying women as “unfit” for leadership further constrain their advancement (Paxton et al., 2020). These challenges are particularly acute in Western Kenya, where customary norms still shape perceptions of authority and constrain women’s entry into formal politics.

Nonetheless, there are growing spaces of optimism. The increased visibility of women in local assemblies, advocacy organisations, and education institutions signals a slow but steady shift in gender relations. Exposure to global women’s movements and the diffusion of feminist discourses through media, Non- Governmental Organisations (NGOs), and faith- based organisations have empowered women to redefine leadership in relational and community driven ways. This redefinition situates leader- ship not only in hierarchical authority but also in service, empathy, and collective responsibility traits often associated with women’s leadership styles in African contexts (Ngunjiri, 2010).

Empirical research in Kenya increasingly highlights the lived realities behind gendered leadership statistics. Genga and Babalola (2023) found that women in the banking sector experienced persistent gender bias, describing a subtle yet pervasive “think manager, think male” culture that shaped promotion pathways and leadership. Despite demonstrating competence, many felt compelled to conform to masculine leadership norms to gain credibility, reflecting broader sociocultural constraints on women’s expression of authority. Similarly, Kasera et al. (2021) analysed women’s participation in rural electoral politics, showing how women are active in campaign mobilisation yet systematically excluded from candidacy and strategy roles. They termed this exclusion a “gendered architecture of politics,” whereby women’s visibility is high but their voice and power remain constrained. This echoes everyday experiences in Western Kenya, where women often support male politicians as organisers or mediators rather than as political contenders.

Njenga and Njoroge (2019) examined cooperative movements in Nyeri County and observed that social expectations particularly regarding domestic responsibilities and limited mobility restricted women’s participation in cooperative leadership. Their findings underscore how culture becomes internalised: women themselves often self-limit by perceiving leadership as socially inappropriate. Shumbamhini and Chirongoma (2025) propose that the African philosophy of Ubuntu, which emphasises interconnectedness and communal well-being, offers a culturally grounded alternative for conceptualising leadership. Within this framework, leadership is relational rather than hierarchical, collective rather than individualistic. In the Kenyan context, particularly in community-based governance, women have leveraged Ubuntu-like values of care, collaboration, and moral integrity to lead in ways that align with cultural expectations while subtly transforming them.

This body of literature provides a nuanced foundation for analysing gendered leadership in Western Kenya. It demonstrates that leadership is both a structural and a cultural phenomenon constructed through interactions among institutions, norms, and personal agency. Theoretical insights from empowerment theory, intersectionality, and relational leadership frameworks are useful in interpreting these dynamics. They suggest that women’s leadership emerges not merely through legal quotas but through cultural negotiation, community affirmation, and everyday practices of resilience and adaptation.

In Western Kenya, where lineage, age, and tradition continue to influence social legitimacy, understanding leadership through a culturally embedded lens becomes crucial. Women leaders navigate between respecting tradition and challenging exclusion, often using relational networks and moral authority to claim leadership spaces. By focusing on these lived, culturally grounded strategies, this study contributes to an anthropological understanding of gender and leadership one that recognises the human agency, emotions, and meanings behind structural change.

METHODOLOGY

The study employed a cross-sectional design and phenomenology to explore leadership learning and development in Western Kenya. Respondents were selected using both simple random sampling (for household questionnaires) and purposive sampling (for key informants and focus group discussions). Quantitative data were collected through questionnaires, while qualitative data was gathered via interviews, focus group discussions, and observations. The data sets were analysed separately but integrated to understand how leadership is influenced by culture and constitutional factors. Two Bantu- speaking ethnic groups, the Luhya and Kisii, were randomly selected from 6 dominant groups in Western Kenya due to their cultural significance in leadership. The study specifically

focused on the Wanga people of Matungu Sub County, known for their Nabongo Wanga Kingdom, to examine how culture impacts leadership. Other subgroups, including the Banyala and Batsotso, were also studied. Using the Morgan and Krejcie formula, 384 cases were selected for questionnaire administration, with a response rate of 94% (361 cases). Additionally, 16 focus group discussions (8 in each county), 25 key informant interviews, and 25 observations were conducted across Kakamega and Kisii Counties.

Theoretical Framework

Social Role Theory (SRT)

Social Role Theory, developed by Eagly (1987), explains how societies assign certain behaviours, expectations, and responsibilities to men and women based on culturally defined gender roles. Over time, these expectations shape what people believe men and women can or should do including who is seen as a “natural leader.” In most patriarchal contexts, men are expected to be assertive, ambitious, and authoritative, while women are associated with nurturing, supportive, and communal roles. In leadership studies, this theory helps to explain why women often face stereotypes that question their ability to lead, especially in political and public life (Eagly & Karau, 2002). When women show confidence or authority, they are sometimes judged as “too aggressive” or “unfeminine,” while men showing the same traits are praised as strong leaders. These biases affect how both men and women view themselves and how others respond to their leadership. In the Kenyan context particularly in Western Kenya Social Role Theory helps to explain why women’s leadership is often viewed through the lens of culture and tradition. For instance, men are typically seen as public decision-makers, while women are expected to influence indirectly through family or community service. Understanding these social expectations provides a basis for analysing how women leaders challenge and redefine traditional gender roles through education, advocacy, and grassroots mobilisation.

Culturally Sustaining Leadership Theory (CSLT)

Culturally Sustaining Leadership Theory (Paris & Alim, 2017) builds on the idea that effective leadership must recognise, respect, and nurture the cultural identities of the communities it serves. Rather than forcing conformity to dominant (often Western or patriarchal) leadership norms, CSLT promotes leadership that values diversity, collective wisdom, and cultural integrity. It sees culture not as a barrier to progress, but as a source of strength and guidance for inclusive change. In practice, this means leaders should use their cultural knowledge and values to inspire transformation from within the community. For example, in Western Kenya, women leaders often draw on local cultural principles such as Ubuntu (shared humanity), obonyore (collective welfare), and mutual respect to frame their leadership as service to the community rather than individual ambition. This culturally grounded approach not only makes leadership more acceptable in traditional societies but also helps redefine what leadership looks like for future generations. CSLT therefore provides a framework for understanding how women navigate and reinterpret cultural norms to sustain their communities while asserting their right to lead. It highlights that leadership is not only about power or position, but about maintaining social harmony, moral integrity, and collective progress values deeply rooted in African communal life. Combining Social Role Theory and Culturally Sustaining Leadership Theory offers a more complete understanding of gender and leadership in the Kenyan context. Social Role Theory helps to explain why gender inequalities persist by showing how social expectations shape opportunities and behaviours. In contrast, CSLT shows how leaders, especially women, can use culture itself as a tool for empowerment and transformation. Together, these theories reveal that cultural norms are not fixed; they can evolve. Women leaders in Western Kenya are not merely breaking traditions they are reworking them. They respect cultural values but also reinterpret them to make leadership more inclusive. This dual framework therefore highlights both the barriers that limit women’s leadership and the creative strategies they use to overcome them.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

Patriarchy And Masculinity On Men To Become Leaders In Western Kenya

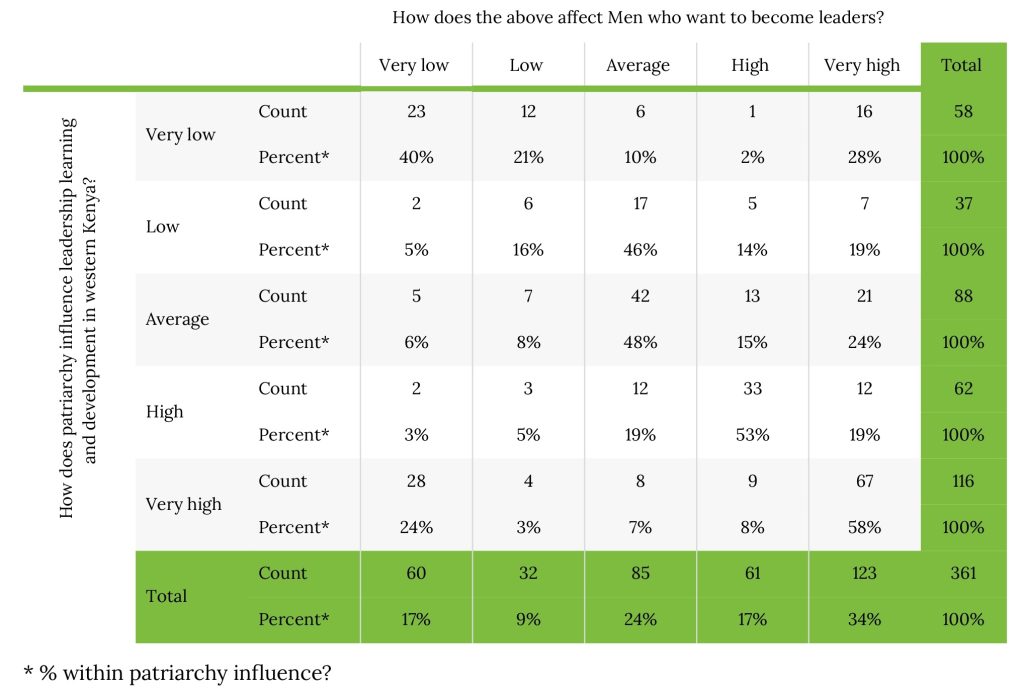

Table 1 reveals a complex and somewhat paradoxical relationship between the perceived influence of patriarchy and its effects on leadership aspirations in Western Kenya. For respondents who believed that patriarchy had a very low influence on leadership learning, 39.7% believed that this had a very low effect on men who aspired to leadership.), However there was a significant portion (27.6%) who noted a very high effect on men aspiring to leadership roles despite saying that patriarchy had very low effect on leadership development and learning. This is counterintuitive, as one would expect a lower influence to correspond with a diminished effect. However, one possible explanation is that while the overall influence of patriarchy appears weak, some aspects of societal structures, such as family inheritance patterns, traditional ceremonies, or male- centric leadership expectations, still exert significant pressure on male leadership ambitions. Additionally, 20.7% reported low effects, while 10.3% mentioned an average effect, further indicating variability influenced by individual or contextual factors. This could reflect a more nuanced reality where patriarchal norms persist even in subtle forms, though less overtly than before.

Table 1: How does patriarchy influence leadership learning and development in Western Kenya? * How does the above affect Men who want to become leaders?

In contrast, others argue that this variation may suggest a different interpretation: that individuals in regions with lower patriarchal influence are more adaptable to modern, egalitarian views of leadership. Some respondents may not perceive patriarchy's impact on leadership as significant because they are in environments where leadership opportunities for both men and women are expanding due to education and socio- economic advancements. This perspective could explain why, despite low perceived patriarchal influence, a notable proportion still reported substantial effects on male leadership aspirations.

Among respondents who felt patriarchy had a low influence, the majority (45.9%) indicated an average effect on men aspiring to leadership. This finding suggests that although patriarchy may not dominate leadership learning and development, it retains a moderate, pervasive impact, subtly influencing leadership pathways. The 18.9% among them who noted a very high effect points to persistent traditional gender expectations in certain areas, where patriarchal structures, though weakened, still shape leadership roles. However, critics of this view argue that the persistence of patriarchal norms in these areas might be overemphasised, and instead, leadership aspirations could be more closely tied to other factors such as economic status, access to education, or exposure to urban, cosmopolitan ideals. This alternative view challenges the assumption that patriarchal influences alone are the primary drivers of leadership dynamics, suggesting that the effects of modernity and global cultural exchanges might also play crucial roles in shaping leadership aspirations.

For respondents who perceived patriarchy’s influence as average, there was a strong consistency, with 47.7% reporting an average effect on leadership aspirations. This predictable correlation suggests that in environments where patriarchy holds moderate power, its impact on leadership development tends to be more uniform. However, a significant 23.9% of them reported a very high effect, which raises the question of whether "average" patriarchal influence could still reinforce strong male-centric leadership aspirations in certain communities. Proponents of this perspective argue that even moderate patriarchal norms can act as invisible social forces, subtly reinforcing male leadership roles through cultural expectations that are passed down generationally.

On the other hand, some may argue that this finding demonstrates a contradiction. In communities where patriarchy is only moderately influential, the expectation would be for men and women to have increasingly equal leadership opportunities. The 23.9% reporting a very high effect could therefore reflect specific local factors such as strong leadership traditions in particular families or clans that do not necessarily indicate widespread patriarchal dominance. These contrasting views highlight the complexity of patriarchy’s influence and suggest that its impact may not be universally felt in the same way across different communities.

Among respondents who viewed patriarchy’s influence as high, there was a strong correlation with 53.2% reporting a high effect on leadership learning and development. This reinforces the idea that in regions where patriarchal values are deeply entrenched, male leadership aspirations are reinforced by these traditional structures. However, a smaller percentage (19.4%) reported an average effect, which could be explained by the fact that even in highly patriarchal settings, external factors such as education, exposure to modern leadership models, or individual ambition may moderate patriarchy's influence. Dissenting opinions might argue that the high impact of patriarchy in these regions should not be overstated, as the global shift toward gender equality in leadership is increasingly influencing even traditionally conservative areas. The presence of average and lower effects might indicate that patriarchal values are being increasingly challenged by new societal norms, particularly among younger generations.

For those who identified patriarchy’s influence as very high, the majority (57.8%) correlated this with a very high effect on leadership aspirations. This suggests that in communities where patriarchal norms are deeply ingrained, leadership roles remain overwhelmingly male- centric. Yet, 24.1% of them reported a very low effect, which could indicate a divergence where certain individuals or sub-groups within these communities are able to defy or reinterpret traditional gender expectations, leading to leadership practices that do not align with strict patriarchal norms. Some scholars argue that this finding is evidence of shifting dynamics in these communities, where education and modernisation are gradually eroding patriarchal strongholds. Others contend that the resilience of patriarchy in these communities remains strong and that the minority reporting low effects may represent a small, isolated segment of the population, rather than a broader trend toward egalitarianism.

The qualitative data from interviews and focus group discussions further illustrate these contrasting views. Participants frequently emphasised the role of cultural rituals and inheritance in shaping male leadership. A participant from Kakamega County stated, “Leadership here is passed down, especially to men in certain families. It’s just expected that boys will take charge.” This aligns with the high effect of patriarchy reported in highly patriarchal communities. However, others noted changing dynamics. An informant in Kisii County reflected, “Things are changing, but for a long time, leadership was just for men; it’s how our elders taught us.” These varying perspectives suggest that while patriarchal traditions remain influential, modern forces such as education, urbanisation, and changing social norms are increasingly challenging these expectations.

The findings of this study align with other research that highlights the complex relationship between traditional gender norms and leadership pathways. For instance, Anyango et al. (2019), in their study on gender and leadership in rural Kenya, found that while patriarchy remained a key determinant of leadership positions, there was an increasing shift toward more gender-inclusive models of leadership, particularly in regions exposed to educational interventions and economic changes. This study mirrors our findings where, even in communities with low perceived patriarchal influence, significant portions of the population still report strong effects on male leadership aspirations, indicating that patriarchy may linger in subtler, less visible ways.

Ntarangwi (2016), who explored cultural practices and leadership in East Africa, argued that in some regions, leadership remains closely tied to male inheritance practices and traditional ceremonies. This parallels our findings, where respondents from regions with strong patriarchal structures noted that leadership roles are often passed down within male-dominated family lineages. One participant’s statement, “Leadership here is passed down, especially to men in certain families,” corroborates Ntarangwi’s argument that leadership structures in rural Kenya often remain male-centric due to cultural inheritance systems, despite changing societal norms.

However, contrasting studies offer a different lens on the role of patriarchy in leadership. For instance, Mbote and Akech (2021), in their examination of leadership dynamics in Kenya’s urban centers, found that while patriarchy historically shaped leadership norms, new urbanisation trends and exposure to global leadership models are increasingly reshaping these norms. Their study suggests that patriarchal influence is waning in urban areas, with more women aspiring to leadership roles. Although this study was situated in Western Kenya, where patriarchal traditions are still significant, the contrasting data on urban areas highlights a key point: even within regions that report high patriarchal influence, modern forces such as education, urbanisation, and gender equality initiatives are beginning to dismantle long-held traditions. This can also explain the responses from some of our participants, particularly in Kisii County, who noted, “Things are changing, but for a long time, leadership was just for men.” Such statements indicate a shift in perception, even in areas with entrenched patriarchal structures.

As a researcher, I found these contrasting views particularly intriguing, especially the variations in responses based on the perceived influence of patriarchy. While some respondents viewed patriarchy as having a diminished effect, they still acknowledged its lingering impact on male leadership aspirations. This paradox echoes Sifuna and Chege’s (2017) research, which argued that in regions undergoing socio- economic transitions, patriarchal norms often evolve into more covert forms, maintaining their influence but in less visible ways. Sifuna and Chege’s work helped me understand how, despite the reported low influence of patriarchy, many respondents in this study still reported significant effects on leadership, suggesting that these norms might be adapting rather than completely disappearing.

Moreover, the findings of this study are corroborated by Oduol (2019), who explored the role of education in challenging patriarchal leadership norms in Kenya’s rural communities. Oduol’s research demonstrated that educational interventions significantly influenced leadership aspirations by providing alternative models of leadership that challenge traditional, male-dominated structures. In this study, education emerged as a key factor in moderating the effects of patriarchy on leadership, particularly in regions where respondents reported low to moderate levels of patriarchal influence. This suggests that educational programs in Western Kenya could play a crucial role in shifting leadership norms, aligning with global trends toward gender parity in leadership.

Patriarchy, Leadership Learning And Development And Its Effects On Women In Western Kenya

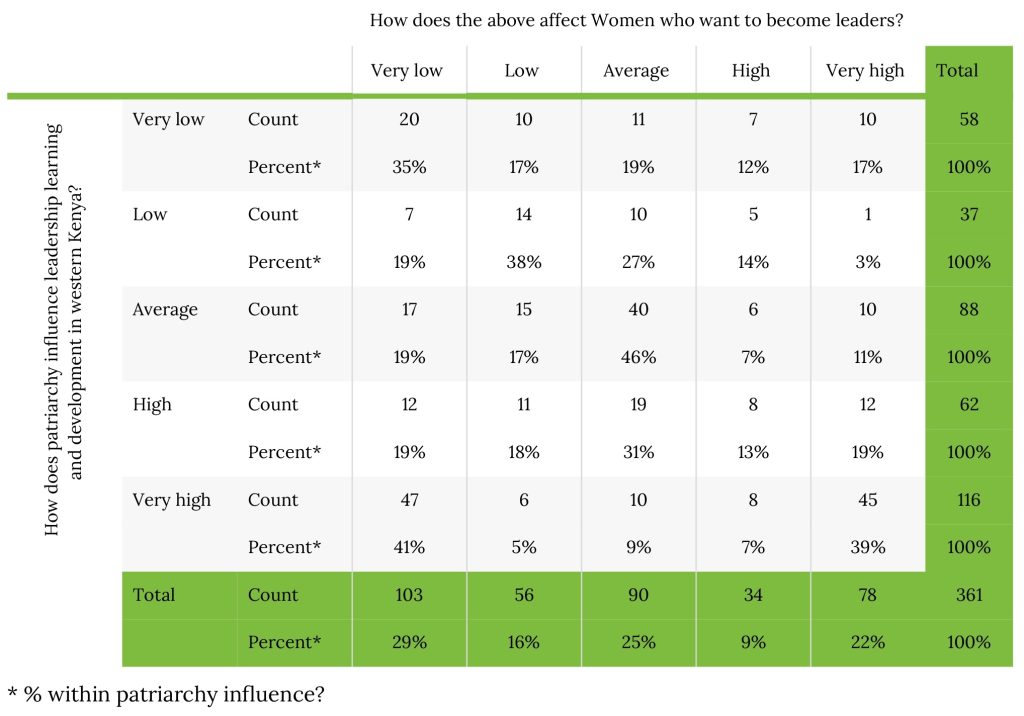

Table 2 illustrates how patriarchy continues to shape women’s leadership learning and aspirations in Western Kenya, though its influence varies widely. The findings reveal that perceptions of patriarchy’s impact range from “very low” to “very high,” suggesting that women’s experiences are far from uniform. Most respondents (34.5%) among those who viewed patriarchy as having a very low influence on leadership learning believed that it had little effect on women’s desire to pursue leadership roles. This finding may indicate that patriarchal barriers are weakening in certain spaces or that women are finding ways to navigate them successfully. As one participant explained, “Women today see leadership as achievable; culture no longer silences everyone.” This observation echoes Nkomo and Ngambi’s (2009) argument that African women increasingly reinterpret gender norms to expand leadership opportunities rather than passively accept restrictions.

Table 2: How does patriarchy influence leadership learning and development in western Kenya? * How does the above affect women who want to become leaders?

However, even among respondents reporting a low influence of patriarchy, some (17.2%) still perceived a high effect on women’s leadership aspirations. This apparent contradiction suggests that even minimal patriarchal attitudes can have an outsized psychological or social impact, especially when reinforced by economic or institutional barriers. Tamale (2020) similarly notes that patriarchal systems endure in subtle ways through everyday practices and beliefs that normalise male dominance, even in settings where formal equality has advanced. Respondents who viewed patriarchy’s influence as average reflected a moderate stance. Many recognised that traditional norms still shape leadership access but do not entirely prevent women from aspiring to lead. This shift may be attributed to expanded education, gender quotas, and leadership mentorship programmes that have begun to soften patriarchal effects (Nzomo, 2015). A participant noted, “Training and women’s groups give us courage to speak and lead.” Such voices demonstrate the gradual transformation of gender roles through collective empowerment and education.

Conversely, those who perceived high or very high patriarchal influence tended to associate it with greater barriers to women’s leadership. For these respondents, patriarchal norms remain deeply rooted in family and community hierarchies, often limiting women’s visibility in decision-making. As Kabeer (2016) observes, such structural inequalities are not evenly distributed: women in rural and traditional settings face stronger cultural restrictions than their urban counterparts. Still, it is notable that even within highly patriarchal contexts, some women reported finding ways to lead. Cornwall and Goetz (2005) highlight this adaptive agency, showing that women often use informal networks, grassroots activism, and social capital to bypass formal patriarchal structures.

In summary, Table 2 presents a complex but hopeful picture. While patriarchy remains influential, its impact on women’s leadership aspirations is gradually being contested through education, empowerment initiatives, and cultural negotiation. This aligns with CSLT, which posits that leadership transformation often begins within, rather than outside culture. Women are not merely rejecting tradition; they are reworking it to create space for inclusive leadership that resonates with community values.

Masculinity Leadership Learning And Development In Western Kenya on Men Who Want To Become Leaders

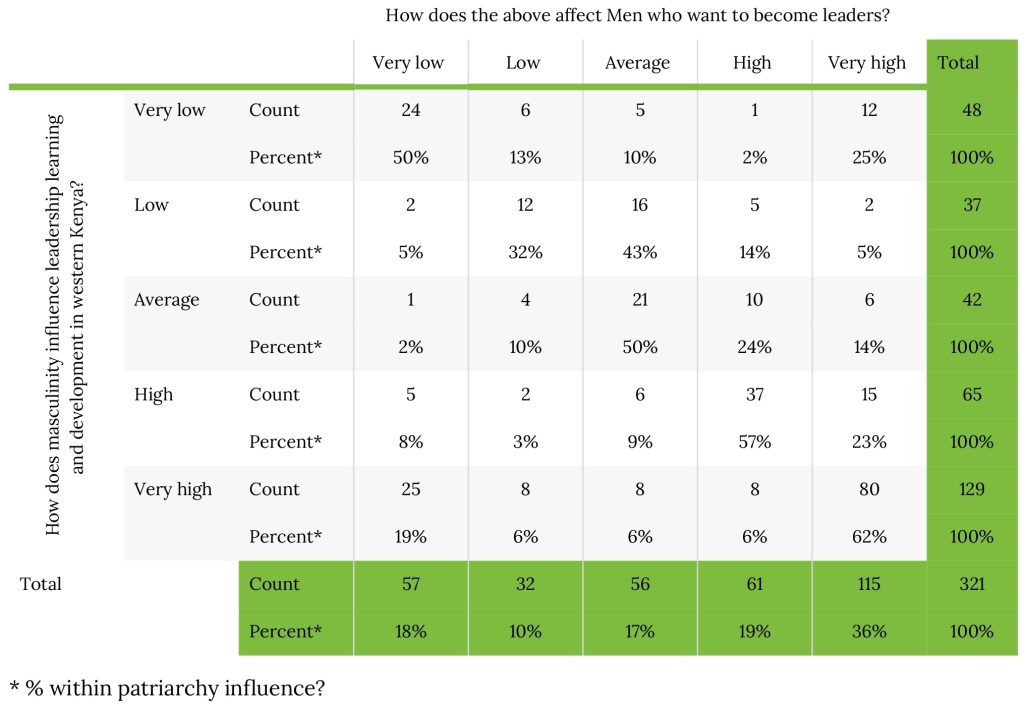

Table 3 presents how masculinity shapes leadership learning and development in Western Kenya. While many (50%) of the respondents who said masculinity had a very low influence on leadership felt that this had a very low effect on the men who want to become leaders, the qualitative data revealed that masculine ideals remain subtly embedded in expectations of what a leader should be. As one male respondent explained, “Even when we say masculinity doesn’t matter, you still have to look tough and firm to be respected.” This echoes Connell’s (2005) concept of hegemonic masculinity, where male dominance operates quietly through cultural assumptions that equate leadership with strength and assertiveness.

Interestingly, a quarter of respondents who rated masculinity’s influence as very low still believed it had a very high effect on men aspiring to lead. This suggests an internalised pressure: even when men deny masculinity’s influence, they continue to perform it subconsciously. Kimmel (2010) describes this as the “invisible script” of masculinity where men feel compelled to embody traits like control and confidence to sustain legitimacy as leaders. These findings point to an underlying contradiction: while overt gender roles are shifting, traditional masculine ideals still define how leadership is perceived and enacted.

Table 3: How does masculinity influence leadership learning and development in Western Kenya? * How does the above affect Men who want to become leaders?

Participants who viewed masculinity as having an average influence largely associated it with an average effect on leadership aspirations. Their responses reveal a gradual cultural shift where leadership is no longer tied exclusively to dominance but increasingly to competence and community trust. Yet, the expectation to project authority remains. As one participant said, “You can lead in different ways now, but people still expect a man to show strength when it matters.” This insight aligns with Messerschmidt’s (2012) work, which argues that evolving masculinities coexist with older ideals, particularly in traditional settings.

Those who perceived masculinity as a strong or very high influence overwhelmingly associated it with stronger effects on leadership. In these cases, leadership was still viewed as a masculine domain, reinforcing the social belief that authority and control are “natural” male attributes. One participant stated, “Here, you can’t lead without being seen as a strong man- it’s just how it is.” These views mirror Messner’s (2007) findings that hegemonic masculinity remains deeply tied to community perceptions of legitimate leadership in conservative societies.

Integrating these findings with global literature, the study reaffirms that masculinity continues to shape leadership expectations through enduring gendered power structures (Acker, 1990; Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). Yet, there is evidence of transformation. Scholars such as Eagly and Carli (2007) describe a shift toward transformational leadership, a style characterised by empathy, collaboration, and inclusivity. Similarly, Ibarra, Ely, and Kolb (2013) show that both men and women who adopt relational and participatory approaches increasingly thrive in leadership roles. These emerging models suggest that men in regions like Western Kenya could benefit from leadership development that encourages emotional intelligence and shared decision- making rather than dominance and control.

Fletcher’s (2004) notion of post-heroic leadership further underscores this transition, advocating for collective and humble forms of leadership that transcend gendered expectations. Within Western Kenya, such a shift aligns with the principles of CSLT, which encourages adaptation rather than rejection of local norms. Men can still embody strength and authority, but in ways that are inclusive, ethical, and community-centered.

From the foregoing presentation, while masculinity remains a strong cultural marker of leadership in Western Kenya, its influence is gradually evolving. Traditional masculine ideals coexist with emerging notions of shared, empathetic, and collaborative leadership. This balance reflects a broader transformation one where leadership effectiveness is increasingly measured not by dominance, but by cultural authenticity and social responsiveness.

Masculinity Leadership Learning and Development In Western Kenya On Women Who Want To Become Leaders

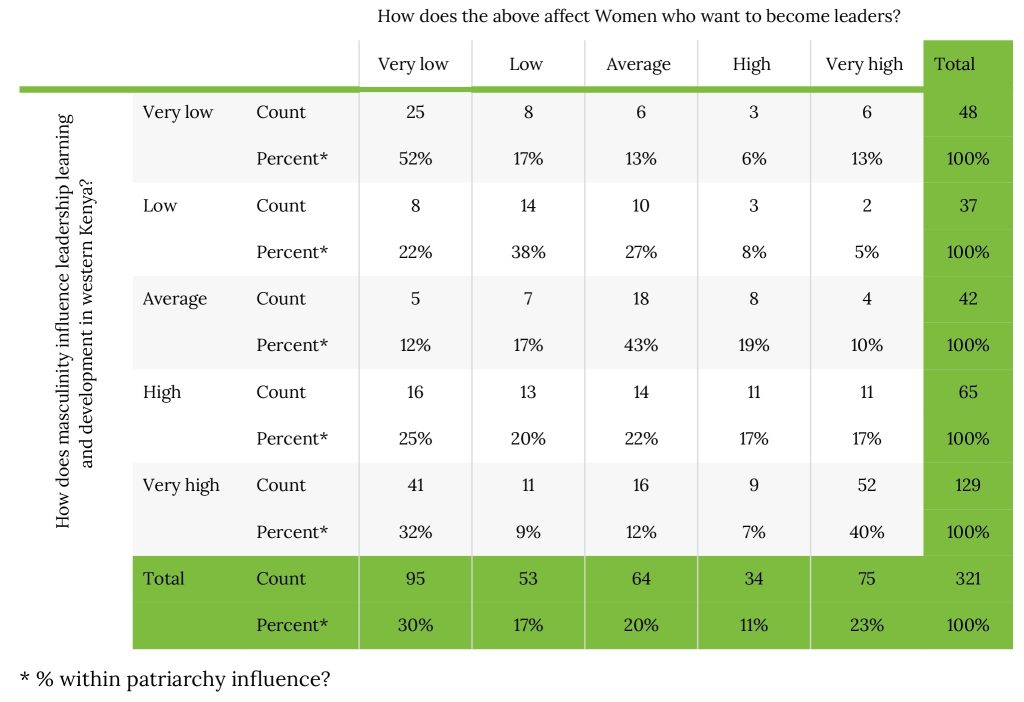

Table 4 illustrates that a majority of respondents (52.1%) who perceived masculinity as having a very low influence on leadership learning and development in Western Kenya believed it had a very low impact on the aspirations to leadership of women. This perception translated into varied implications for women’s aspirations toward leadership. Over half of the participants noted that reduced masculine influence corresponded with increased space for women’s participation in leadership. This observation resonates with Oduol (2007), who argues that in patriarchal societies, when masculine dominance is relaxed, women often gain new though still limited opportunities to lead. However, 12.5% of these respondents paradoxically believed that even when masculinity appears weak, its residual cultural power continues to shape women’s ambitions. This highlights how patriarchal norms may persist subconsciously, even when their overt influence diminishes (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005).

Similarly, 37.8% of respondents who perceived masculinity as having a low influence also reported a correspondingly low effect on women’s leadership prospects. This finding supports Githinji’s (2012) view that cultural perceptions of gender, even when softened, subtly constrain women’s public participation.

Table 4: How does masculinity influence leadership learning and development in Western Kenya? * How does the above affect Women who want to become leaders?

Yet, 21.6% associated the same “low influence” of masculinity with an even lower impact on women’s leadership suggesting a nuanced reality where the erosion of male dominance may, in some cases, open genuine pathways for women. These contrasting responses capture the transitional nature of Western Kenya’s cultural landscape, where gender norms are neither static nor uniform across communities (Mkutu et al., 2021).

Of those who perceived masculinity as having an average influence (42.9%) believed it had an average effect on women’s leadership aspirations. This “middle ground” reflects an ongoing tension in which patriarchal ideas continue to influence leadership learning but coexist with emergent forms of gender inclusivity. Ngugi (2014) previously observed that cultural practices tied to masculinity still profoundly affect women’s leadership trajectories, especially in rural Kenya. The divergence between his findings and the current study may signal shifting norms or generational differences within Western Kenya, underscoring the importance of localised gender studies (Ampofo & Boateng, 2011).

When masculinity was perceived as having a high or very high influence, responses were sharply polarised. Those who saw masculinity as “very high” also reported a similarly high suppression of women’s leadership (40.3%). This reinforces Odinga’s (1967) early observation that patriarchal systems systematically restrict women’s participation in authority structures. Yet, 31.8% of those respondents held the opposite view that even with high masculine dominance, women’s leadership was minimally affected. This apparent contradiction may reflect shifting power dynamics in which women increasingly assert leadership despite cultural resistance. Similar patterns have been noted by Nnaemeka (2005), who argues that African women often exercise “nego-feminism”, a form of negotiation and resilience within male-dominated systems.

Focus group discussions (FGDs) provided deeper cultural insights. Participants observed that Kenya’s progressive Constitution simultaneously protects cultural heritage (“mila yetu”) while guaranteeing gender equality. This duality means that the same legal framework that empowers women can also reinforce traditional male authority. This aligns with Cornwall (2005), who contends that legal reforms alone cannot dismantle deeply entrenched social hierarchies. In Kakamega, for example, women expressed frustration that while the Constitution affirms equal opportunities, it also legitimises traditional structures like the Nabongo Kingdom that remain patriarchal in composition and practice.

An even more delicate contradiction emerged regarding the ban on female circumcision. Both male and female respondents noted that, traditionally, initiation rites were seen as legitimising women’s social maturity and readiness for community leadership. While the ban rightly protects women’s health and dignity, its unintended consequence has been the loss of certain cultural pathways to recognition as leaders. This echoes Amadiume (1997), who argues that colonial and postcolonial legal regimes often misunderstood or erased indigenous gender systems that once enabled female authority. Key informant interviews revealed both resistance and progress. Older male respondents from Kakamega argued that “a woman cannot be a leader” due to long-held cultural divisions of labour. Yet, the increasing visibility of female assistant chiefs and village elders demonstrates gradual but tangible shifts in leadership norms. This transition aligns with Chilisa and Ntseane (2010), who note that African women are increasingly redefining leadership through community-based and moral authority rather than positional power.

Finally, the study identified enduring forms of traditional female leadership such as women guiding others on moral and social matters though these roles remain confined largely to domestic or informal spaces. As Tamale (2004) contends, traditional leadership systems often undervalue women’s contributions by categorising them as “private” rather than “public” leadership. Nonetheless, the growing presence of women in formal administrative roles suggests an evolving redefinition of authority, where women’s participation is not merely tolerated but increasingly normalised.

Overall, the findings portray a complex but hopeful picture. Masculinity continues to shape leadership learning and development in Western Kenya, but its dominance is gradually being renegotiated. While entrenched gender norms remain, new spaces for women’s agency are emerging, supported by education, constitutional reforms, and shifting generational attitudes. As Kenya continues to balance cultural preservation with gender equality, the challenge lies not in erasing tradition but in reimagining it to accommodate inclusive leadership ideals that reflect the aspirations of all citizens.

These findings make it clear why Social Role Theory (Eagly, 1987) and Contextualised Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977) are useful for understanding leadership in Western Kenya. Social Role Theory helps explain how cultural expectations about men and women influence who is seen as a leader. Men are often expected to be strong, assertive, and in control, while women are associated with care and support. These expectations affect leadership opportunities, even when communities are starting to change. Contextualised Social Learning Theory shows how these roles are learned and passed on through everyday social interactions. People watch how others act and learn what is acceptable. For example, when women see other women successfully taking leadership positions, such as female assistant chiefs or village elders, they begin to imagine themselves in similar roles. Over time, these examples can change community attitudes about who can lead.

Together, the two theories help us see that leadership is not just about individual ability or ambition. It is shaped by social norms, cultural expectations, and learning through observation. Leadership learning and development happen as people observe, practice, and adjust their behaviours in their social environment. In Western Kenya, this means that women are gradually finding ways to navigate traditional barriers, while men are also learning to adapt to more inclusive leadership expectations. This connection between theory and practice shows that efforts to promote women’s leadership need to consider both cultural expectations and the social learning processes that reinforce them. Programs that provide role models, mentorship, and community support can help challenge traditional gender norms and open spaces for more inclusive leadership. By linking these findings to theory, we can better understand not only the challenges women face but also the strategies that allow them to succeed in leadership roles.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study highlights how leadership in Western Kenya is closely linked to cultural practices, values, and traditional institutions. Leadership development is not a single event but a process shaped by socialisation, mentorship, and cultural activities, such as initiation rites. The Nabongo Kingdom in Kakamega County and initiation practices in Kisii County illustrate how traditional structures continue to influence leadership selection today. The findings show that leadership emerges from the interaction of cultural institutions, community rituals, and learning experiences rather than being solely the result of individual effort. This aligns with Hazy’s (2008) idea of leadership as a complex system, where multiple factors cultural expectations, guidance from elders, and community engagement work together to shape leaders.

Key conclusions include: first, the identification of potential leaders often begins in childhood, with families and communities playing a central role through mentorship and cultural norms. Second, the use of technology in Western Kenya is enhancing communication between leaders and communities while helping preserve cultural heritage. Finally, leadership remains community-centered, with most leaders focused on local development, though some also contribute at national and continental levels. This study contributes to the literature on culturally-informed leadership, supporting the work of Dorfman et al. (2012), Jogulu (2010), and Inyang (2009), who emphasise that understanding cultural influences is essential for effective governance. It also responds to Edwards and Turnbull (2013), who argue that leadership learning processes are underexplored. By examining the role of culture in leadership development, this research provides practical insights into how traditional values can support effective and inclusive leadership today.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Engage Elders in Gender-Inclusive Mentorship Programs: Establish mentor- ship programs involving both male and female elders to pass on leadership skills, cultural knowledge, and values. This will preserve cultural integrity while promoting inclusive leadership for both men and women.

- Promote Gender and Youth Inclusivity in Leadership: Ensure women, men, and youth have equal opportunities to participate in leadership. Promote diversity in leadership to allow women and youth to contribute to political and cultural decision-making locally and nationally.

- Strengthen Culturally Inclusive Leadership Structures: Recognise and integrate leadership practices that respect both cultural heritage and gender inclusivity. Collaborative frameworks that honor tradition while adhering to legal and constitutional requirements can enhance community engagement and socio-political development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I acknowledge project sponsors, the Tanzania Government through Uongozi Institute; Plot No. 62, Msasani Road, Oyster Bay P.O. Box 105753, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania for funding this study.

REFERENCES

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4(2), 139–158.

Adichie, C. N. (2017). Dear Ijeawele, or a feminist manifesto in fifteen suggestions. Anchor Books.

African Union. (2020). Agenda 2063: The Africa we want. African Union.

ALIGN Platform. (2019). Gender Report: Building Bridges for Gender Equality. Align Platform. https://www.alignplatform.org/resources/gender-report-building-bridges-gender-equality

Amadiume, I. (1997). Reinventing Africa: Matriarchy, religion, and culture. Zed Books.

Ampofo, A. A., & Boateng, P. (2011). Localized gender studies: A case for contextual research in Ghana. Gender & Development, 19(3), 351– 362.

Anyango, P., Chege, M., & Omondi, L. (2019). Gender and leadership in rural Kenya: The influence of patriarchy on women's political participation. Journal of Gender and Development Studies, 10(3), 112–125.

Aringo, S. M., & Odongo, O. (2025). Women in Kenyan Political Culture in Light of the Ubuntu Spirit. International Journal of Geopolitics and Governance, 4(1), 70-82. https://doi.org/10.37284/ijgg.4.1.2802

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Chilisa, B., & Ntseane, P. G. (2010). African women redefining leadership through community-based and moral authority. International Journal of Educational Development, 30(4), 346–355.

Connell, R. W. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859.

Cornwall, A. (2005). Democratic governance and gender: The challenge of change. Journal of International Development, 17(7), 903–912.

Cornwall, A., & Goetz, A. M. (2005). Democratising democracy: Feminist perspectives on power and transformative politics. Critical Asian Studies, 37(4), 539–559.

Cornwall, A., & Rivas, A. M. (2015). From gender equality to women’s empowerment: The history of a concept. Development, 58(2–3), 195–201.

Council of Governors. (2022). Institutionalising gender-responsive budgeting and mentorship: Initiatives of the Council of Women Governors. Council of Governors.

Dorfman, P. W., Javidan, M., Hanges, P., Dastmalchian, A., & House, R. (2012). Globe: A twenty-year journey into the study of culture and leadership. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 504–514.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. (2007). Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 85(9), 62–71.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598.

Edwards, J., & Turnbull, S. (2013). The underexplored process of leadership learning. Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(4), 1–4.

Fletcher, J. K. (2004). The paradox of post- heroic leadership: An affirmative deconstruction. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(5), 647–661.

Genga, J. A., & Babalola, S. O. (2023). Gender bias and the ‘think manager, think male’ phenomenon in the Kenyan banking sector. East African Management Review, 12(1), 1–15.

Githinji, S. (2012). Cultural perceptions of gender and their subtle constraint on women’s public participation in Kenya. African Review of Economics and Finance, 3(2), 154–171.

Gumo, S. (2018). The Traditional Social, Economic, and Political Organization of the Luhya of Busia District. Scholars Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 6(06), 1245–1257. https://doi.org/10.36347/sjahss.2018.v06i06.010

Hazy, J. K. (2008). The leadership system: An initial assessment of the conceptual framework. Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 10(1), 58–78.

Ibarra, H., Ely, R. J., & Kolb, D. M. (2013). Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 91(4), 16–18.

IEBC. (2022). Kenya general election report. Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission.

Inyang, B. J. (2009). The challenge of culturally informed leadership for effective governance. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(12), 163–172.

Jogulu, U. (2010). Culturally informed leadership for effective governance. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 5(3), 227–236.

Kabeer, N. (2016). Gender, policy and inequality: Briefing paper for the development committee. Journal of International Development, 28(4), 565–586.

Kamau, E. W. (2010). Leading from within: Women's agency and emerging leadership roles in Kenyan community settings. Journal of African Women's Studies, 2(1), 34–49.

Kasera, L., Ndung’u, R., & Wanjiku, M. (2021). The gendered architecture of politics: Women's roles and exclusion in rural electoral processes in Kenya. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 13(2), 65–78.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2021). The status of the two-thirds gender rule implementation in Kenya. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

Kenya Yearbook Editorial Board. (2022). Martha Karua – Kenya’s iron lady of politics. Kenya Yearbook Editorial Board.

Kimmel, M. S. (2010). Guyland: The perilous world where boys become men. Harper Perennial.

Krook, M. L., & Restrepo Sanín, J. M. (2020). The perpetuation of violence against women in politics. European Journal of Politics and Gender, 3(2), 163–182.

Kuada, J. (2010). Culture and management in Africa. Sage Publications.

Mbote, P., & Akech, M. (2021). Leadership dynamics in Kenya’s urban centers: The impact of urbanization on patriarchal norms. Urban Studies and Development Review, 6(1), 45–60.

Messerschmidt, J. W. (2012). Masculinities and crime: A critique and reconceptualization. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Messner, M. A. (2007). The masculine order of things: The hidden history of the American sports bar. Gender & Society, 21(6), 859–882.

Mikell, G. (1997). African feminism: The politics of survival in sub-Saharan Africa. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Minja, A. W., Kimani, B. N., Makhamara, E. D., Gachanja, S. K., Moi, T. C., Mdoe, R. J., Oringo, G. E., & Onditi, J. L. (2025). Capacity-building programs and affirmative action: Reshaping leadership structures for inclusivity in Kenyan governance. Journal of Public Policy and Governance, 9(3), 145–160.

Ministry of Public Service, Gender and Affirmative Action. (2022). Impact assessment of the Women Enterprise Fund and Uwezo Fund. Ministry of Public Service, Gender and Affirmative Action.

Mkutu, K., Wanjala, S., & Bokea, F. (2021). Gender norms, political violence, and the transitional cultural landscape in Western Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 15(2), 201–222.

Mutinda, M., Magutu, J., & Tshiyoyo, M. (2025). Determinants of Socio-Economic Empowerment of Women Traders in Nairobi County: Case of Kenya Trade Policy Financial Inclusion Strategies. Journal of the Kenya National Commission for UNESCO, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.62049/jkncu.v5i1.222

Mwaniki, S. (2017). Prof. Anyang’ Nyong’o and Lupita Nyong’o: Western Kenya's evolving contribution to national and continental leadership narratives. The East African Chronicle, 5(2), 30–45.

National Gender and Equality Commission. (2023). Annual report 2022–2023. National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC). https://www.ngeckenya.org/Downloads/NGEC%202022-2023%20Annual%20Report%20Final%20.pdf

Ngugi, P. (2014). Cultural practices tied to masculinity and their profound effect on women’s leadership trajectories in rural Kenya. Journal of Gender Studies, 23(3), 304–318.

Ngunjiri, F. W. (2010). Women’s spiritual leadership in Africa: Tempered radicals and critical servant leaders. State University of New York Press.

Njenga, F. W., & Njoroge, A. K. (2019). Social expectations, domestic responsibilities, and constraints on women’s cooperative leadership in Nyeri County, Kenya. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 7(1), 1–10.

Nkomo, S. M., & Ngambi, H. (2009). Emerging leadership models in Africa: The role of cultural frameworks. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 9(2), 173–193.

Nnaemeka, O. (2005). Nego-feminism: Theorizing, practicing, and critiquing gender in Africa. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 29(2), 357–381.

Ntarangwi, M. (2016). Cultural practices and leadership in East Africa: Beyond the colonial legacy. Routledge.

Nzomo, M. (2011). Impacts of women in political leadership in Kenya: Struggles for participation in governance through affirmative action [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Nairobi.

Obara, M., & Nyanchoga, S. (2025). Clannism and political representation among the Abagusii of Kisii County, Kenya (1907–2022). Cuea Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 2(1).

Oduol, J. (2007). The relaxation of masculine dominance and women’s limited opportunities to lead in patriarchal societies. Feminist Africa, 8(1), 12–25.

Oduol, J. (2019). The role of education in challenging patriarchal leadership norms in Kenya’s rural communities. African Journal of Rural Development, 4(2), 101–115.

Odinga, O. (1967). Not yet Uhuru: The autobiography of Oginga Odinga. Heinemann.

Ogbodo, E. C., Obidike, C. E., & Nwokolo, I. C. (2022). Patriarchal structures and traditional norms: Revisiting leadership in African societies. African Studies Quarterly, 21(3), 45–62.

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

Paxton, P., Hughes, M. M., & Painter, M. (2020). Women, politics, and power: A global perspective. SAGE Publications.

Pulselive. (2025). Mukhisa Kituyi biography: education, political career, leadership. Pulselive.

Republic of Kenya, [RoK]. (2010). The 2010 Constitution. Government Printer.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J. (2004). Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical analysis of gender inequality. Gender & Society, 18(4), 510–536.

Shumbamhini, N., & Chirongoma, L. (2025). Ubuntu philosophy as a culturally grounded alternative for relational leadership in Africa. Journal of African Culture and Society, 8(2), 99– 115.

Sifuna, D. N., & Chege, M. (2017). Socio- economic transitions and the evolution of patriarchal norms in Kenya. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 9(3), 190–205.

Sow, F. (2019). Gender-inclusive leadership, peacebuilding, and sustainable development: Lessons from Rwanda, Ethiopia, and South Africa. African Security Review, 28(4), 385–400.

Tamale, S. (2004). Eroticism, sensuality, and 'women's empowerment' in contemporary Africa. Feminist Africa, 4(1), 7–20.

Tamale, S. (2020). Decolonisation and afro- feminism. Daraja Press.

Tripp, A. M., Kwesiga, J., Mbugua, E., & Tadesse, S. (2009). African women’s movements: Transforming political landscapes. Cambridge University Press.

UN. (2016). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations.

UN Women. (2023). Gender equality in leadership and political participation in Kenya: Progress and challenges. UN Women.

UN Women. (2025). Global leadership trends and women's political participation. UN Women.