INTRODUCTION

This paper analyses the Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations (ZHOCD) national dialogue initiatives from 2017 to 2021. While reference is made to initiatives before 2017, the paper focuses on the inclusivity or lack thereof in the ZHOCD initiatives surrounding national dialogue after 2017. The paper reviews selected pastoral letters issued during that period, tracing the inclusivity in the Church’s communication and recommendations for national dialogue. It also examines the specific dialogue initiatives pursued in collaboration with other political and non-political actors. The paper contributes to the ongoing conversations on national dialogue in Zimbabwe. It discusses the concept of inclusivity, noting its overstated significance in national dialogue. The paper observes that while inclusivity is at the core of national dialogues, at times it leads to mistrust among stakeholders from diverse backgrounds. Thus, inclusivity can breed ineffectiveness in national dialogue. Yet, the ZHOCD is also accused of its failure to formally accommodate other key stakeholders, such as the military and non- ZHOCD faith actors, in its initiatives. The ZHOCD did not develop a formal, systematic, and predictable engagement strategy with the government. This paper, therefore, asks: To what extent did the ZHOCD’s initiatives between 2017 and 2021 adhere to the principle of inclusivity, and what do its successes and failures reveal about the challenges of implementing inclusive peace in a polarised political environment?

BACKGROUND

In 2017, a new administration in Zimbabwe was ushered in with the assistance of the military. On the eve of the political transition on 15 November 2017, the ZHOCD issued a pastoral statement recommending a comprehensive and inclusive national dialogue to resolve the various challenges that led to the overthrow of President Robert Mugabe. This marked a deliberate journey of the ZHOCD to mobilise the nation towards national dialogue (ZHOCD, 2017). Subsequently, in 2019, the ZHOCD formalised the national dialogue process through a National Leaders' Prayer Breakfast Meeting. Later in 2019, the ZHOCD offered a landmark proposal, the Sabbath Call to the nation (ZHOCD, 2019). The Sabbath Call proposal culminated in the formation of the National Convergence Platform (NCP) that brought together churches and other non-state and non-political actors to facilitate national dialogue. Meanwhile, dialogues with specific stakeholders continued, including with individual political parties, the military, and other religious actors. Yet, those dialogues remained ad hoc.

The ZHOCD argued in its communications that the previous initiatives, before 2017, towards national dialogues in Zimbabwe, led by various actors, were neither comprehensive nor inclusive, hence produced unsustainable solutions. Thus, the ZHOCD pursued an idea of inclusive and comprehensive national dialogues as a way of addressing the deep-seated national challenges. The current paper, thus, assesses the inclusiveness of the ZHOCD approaches and critiques the concept of inclusivity in national dialogue. For the purpose of this paper, inclusivity relates to deliberate and systematic actions to involve all key stakeholders in the national dialogue processes. These include political parties, non-ZHOCD faith actors, civil society, the military, academia, and other interest groups such as people with disabilities, women and youth.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Scanning through the literature, one notes that ZHOCD and national dialogue in Zimbabwe were covered in the media (mainly the ZHOCD Pastoral Letters and Statements, and academic work. Yet, one does not come across work that focuses on the assessment of ZHOCD’s inclusivity from 2017 to 2021. Thus, the current study contributes to the conversations on the principle of inclusivity in national dialogue. It interrogates the concept of inclusivity from the perspective of ZHOCD and that of an ‘insider- outsider’.

Vengesai (2021) notes that the ecumenical bodies in Zimbabwe can be divided into four major categories. These are the Zimbabwe Catholic Bishops Conference (ZCBC), Zimbabwe Council of Churches (ZCC), Evangelical Fellowship of Zimbabwe (EFZ), and the African Independent Churches (AICs) represented by several para-church organisations and networks. For this study, the Union for the Development of Apostolic Churches in Zimbabwe and Africa (UDACIZA) represents the AICs in the ZHOCD. Vengesai (2021) attempts to characterise some of the AICs members as radical, internationally connected, and linked to the ruling party, the Zimbabwe National African Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF). Thus, the ZHOCD (which is made up of the ZCBC, ZCC, EFZ, and UDACIZA) claims to represent the majority in Zimbabwe. In a Pastoral Statement, the ZHOCD says:

Together, these Christian bodies represent more than 80% of the Zimbabwean population. The ZHOCD has its origins in the Heads of Denominations (HoD), which was a loose coalition established in the early missionary periods when the various heads of denominations came together to coordinate their policy in engagement with the state and in sharing perspectives on how missionary work could be executed (ZHOCD, 2021: p1).

The ZCBC is a Catholic institution, the ZCC is made up of Protestant Churches, the EFZ’s members are the Pentecostal ones, while the UDACIZA is composed of indigenous churches. Vengesai (2021) notes that ZHOCD’s main objective is to limit the denominational boundaries among Christians in Zimbabwe and promote unity of purpose when responding to national issues. The current study extends the analysis of the objective in relation to other non-ZHOCD members, including civil society.

Gumbo and Shava (2021) note what they call the ‘exclusivity’ tendencies of ZHOCD national dialogue strategies; however, they do not comprehensively pursue that argument as they only make mention of it. Thus, the current study complements them through a deliberate discussion of the concept of inclusivity in national dialogue pursued by the ZHOCD through a deeper examination of their claims of the exclusivity of the Church’s approaches.

Planta, Prinz and Vimalarajah (2015) comprehensively discuss the concept of inclusivity in national dialogue. They particularly focus on identifying the risk of overestimating the ‘capacity of inclusion’ with national dialogues. Planta et al (2015) cite examples from Yemen and South African national dialogues, among others. By analysing the role and meaning of inclusivity in the context of national dialogues, their work addresses the core dilemmas of national dialogue processes. Planta et al (2015) note the tensions related to effectiveness, representation, legitimacy, power balances, and ownership in national dialogue. They conclude by drawing a balance between the challenges and benefits of inclusivity in national dialogue.

Mandikwaza (2025) acknowledges the increasingly recognised role of national dialogues as a tool to resolve political conflicts. He offers a theoretical framework for national dialogues. Hedraws insights from social contract, consociationalism, and conflict transformation theories. While Mandikwaza (2025) pretested his theoretical framework using the Zimbabwean case, he deliberately ignores the role of the ZHOCD in the national dialogue process in Zimbabwe. Therefore, his analysis of the Zimbabwe case study is incomplete without the visibility of the ZHOCD.

Mujinga (2023) analyses the ZHOCD’s theological justification of the Sabbath call, challenging Church leaders for muting their prophetic voices. The concept of Sabbath is rooted in the biblical creation stories when God is said to have rested on the ‘Sabbath Day’. As noted later, the ZHOCD conceptualisation of the Sabbath was challenged by some actors. Mujinga (2025) further accuses the ZHOCD of its failure to raise critical issues, directed at the political leaders, to resolve challenges of the country’s elections, which have been characterised by mistrust and intimidation. Thus, Mujinga fails to do a holistic analysis of the ZHOCD national dialogue approach. Mujinga (2025) opts to focus on election challenges emanating from the Sabbath call proposal. However, the current study acknowledges Mujinga’s analysis but further discusses the Sabbath call within the broader ZHOCD national dialogue frame.

The Centre for the Advancement of Rights and Democracy (CARD) (2024) also discusses the significance of inclusivity and transparency in national dialogue with particular focus on Ethiopia. The CARD (2024) argues that inclusiveness in national dialogue is crucial for legitimacy, comprehensive solutions, and conflict prevention. Furthermore, inclusivity enhances the credibility of national dialogue processes, and it allows for a holistic understanding of complex issues. Inclusivity also helps mitigate tensions that arise if some sections of the population feel excluded. The ZHOCD also emphasised inclusivity for the comprehensive resolution of the deep-seated challenges the Church noted in Zimbabwe.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

National dialogues have gained currency as tools for resolving internal social, economic, and political crises (Murray & Stigant, 2021, cited in Mandikwaza, 2025). They are known as ‘national’ because of their national outlook, national ownership tag, legitimacy, led by national institutions and covering all provinces. Central to successful national dialogues are their inclusivity, transparency, credibility of conveneors, public participation, adequacy of resources, availability of deadlock-breaking mechanisms, and implementation of outcomes strategies (Murray & Stigant, 2021, in Mandikwaza, 2025).

Yohannes and Dessu (2020) define national dialogues as nationally owned political processes aimed at generating consensus among a broad range of national stakeholders in times of transitioning out of deep political crises and in post-war situations. They are convened to address political, economic, and social crises, as well as improve the legitimacy of public institutions. Ideally, national dialogues should lead to political transition and stability in a country. National dialogues provide potential for meaningful conversations about the underlying drivers of conflicts. (Stigant & Murray, 2015). Planta et al (2015:4) define national dialogue(s) as an “attempt to bring together all relevant national stakeholders and actors (both state and non-state), based on a broad mandate to foster nationwide consensus concerning key conflict issues”.

Yohannes and Dessu (2020:8) posit that inclusivity is “one of the most critical defining factors of national dialogues. Most of the existing literature stresses that national dialogues can only be transformative if they genuinely include different sections of society.” In addition, Yohannes and Dessu (2020:8) attempt to define inclusivity as referring to “convening a broad set of stakeholders and accommodating divergent interests and needs”. For them, the political elite (government and opposition actors) and occasionally, the military are critical stakeholders in national dialogues. They also add civil society, women, youths, faith actors, business, and traditional leaders into their characterisations (s). Stigant and Murray (2015) add that to maximise the dialogue’s potential to address the real drivers of conflict, all key interest groups should participate. The Yemen 2013-14 National Dialogue Conference (NDC) is noteworthy for its inclusion of a broad set of stakeholder groups (Stigant & Muray, 2015).

In its definition of national dialogues, the Inclusive Peace and Transition Initiative (2017) also emphasises inclusivity. The initiative indicates that national dialogues provide an inclusive, broad, and participatory official negotiation format, which can resolve political crises and lead countries into political transitions. (Peace and Transition Initiative, 2017). Although arguing that the Yemen NDC was a failure, Elayah and Schulpen (2016) go against several scholars who regard it as a success story. In their diagnosis of the Yemen NDC, Elayah and Schulpen (2016), however, note the strengths of the process in its inclusivity. They note the inclusion of societal groups (women and youth) invited, who were denied a voice for a long time, as truly revolutionary.

Planta et al (2015:4), however, caution against overstating inclusivity’s effectiveness as a principle. They argue:

There is both the risk of overestimating the National Dialogues’ capacity for inclusion, as well as the transformative impact of an inclusive process design. Although we assume that the principle of inclusivity possesses intrinsic qualities… in practice, it might not necessarily be the case that more inclusivity equals better outcomes.

Planta et al (2015) then recommend further assessment of the assumption that national dialogues are an inclusive process. Furthermore, the authors advise that any discussion on ‘inclusivity’ must go beyond the value “attributed to the principle itself and also critically consider the challenges and dilemmas that emerge with increased social inclusivity in negotiation and transformation processes (e.g. decreasing efficiency, inclusion of anti- democratic forces, the risk of manipulation by elites, cosmetic participation, etc).” (Planta et al, 2015: 4).

The analysis of the ZHOCD approaches is framed using insights from conflict transformation theory, particularly the emphasis on creating platforms for dialogue that include actors from all levels of society (Gumbo & Shava, 2021). The ZHOCD ‘dialogue triangle’ is assessed against this framework to determine its theoretical coherence and practical limitations.

ZHOCD NATIONAL DIALOGUE FRAMEWORK

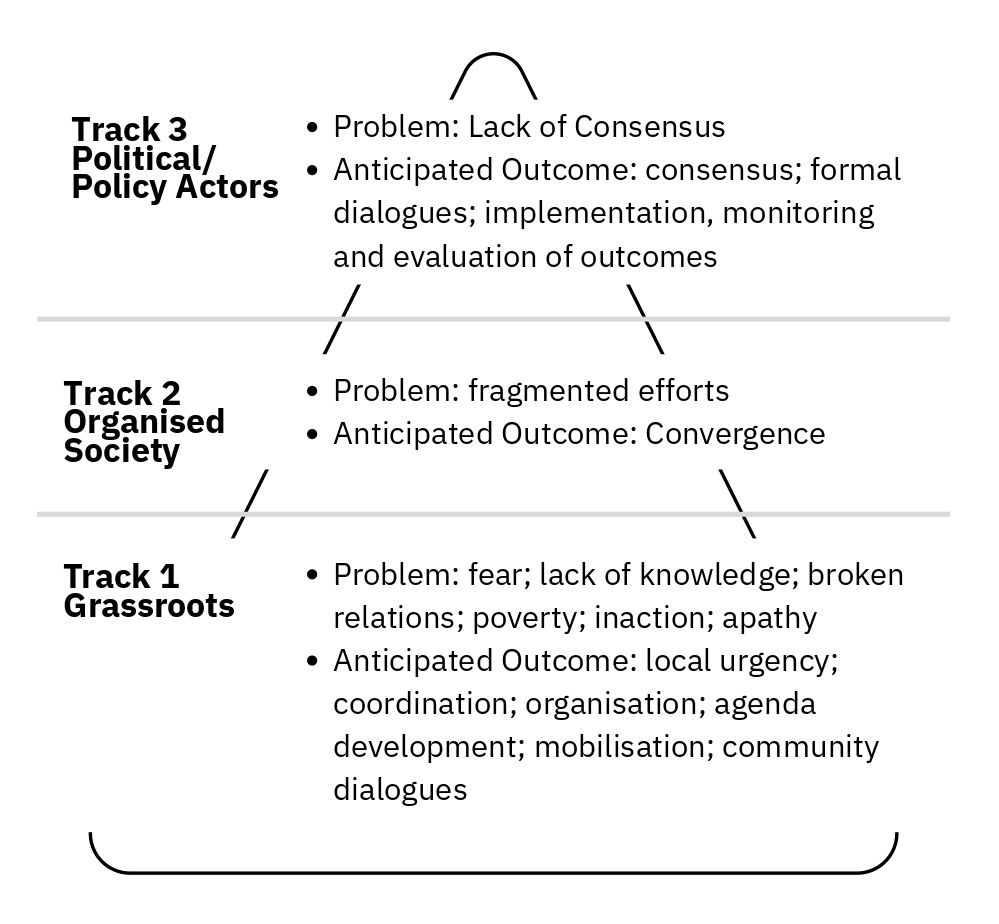

Gumbo and Shava (2021) note that the ZHOCD pursued a comprehensive and inclusive national dialogue. Thus, the ZHOCD advocated for an inclusive, broad-based, comprehensive, and transformative national dialogue, a consistent language captured in its several communications between 2017 and 2021. It developed an understanding that the national dialogue process should happen at three levels: community level to restore citizen agency, organised society level to strengthen convergence amongst non-political actors, and at policy and political actors’ level to achieve policy convergence (Gumbo & Shava, 2021). Its national dialogue framework is presented pictorially through a ‘dialogue triangle’ (Figure 1).

The lowest level, broad in shape, represents ordinary community members who have been affected by poverty, fear, lack of knowledge, inaction, broken relations, and other social and economic challenges, as noted in all key ZHOCD statements under review in this paper. Thus, the ZHOCD hoped to mobilise the community members for coordinated approaches to local and national issues. The organised society level is represented by civil society, academia, and independent institutions. Yet, the major challenge is that these actors approach national issues in a fragmented manner without coordination (Gumbo & Shava, 2021). Thus, the ZHOCD strategy is to influence convergence, where collective reflections on the national question will lead to comprehensive solutions that address the deep-seated problems manifesting in different forms.

At the top are the policy or political actors who, however, have not agreed on the nature of the national problems and ways of addressing these. Lack of consensus remains an obstacle to progress in Zimbabwe. Thus, issues raised by organised society are being formally tabled before the political actors for dialogue by the ZHOCD, leading to common outcomes. Thus, the ZHOCD inclusivity principle must be understood within this triangle framework.

Through the ‘dialogue triangle’. The ZHOCD envisioned a change driven from below through the middle level to the policy actors’ stage, where implementation of dialogue outcomes is realised. With an organised, coordinated, and activated base, critical issues affecting the nation can be mobilised. These will then be analysed and sifted by the organised society, incorporating various sectoral interests represented at that level. The ZHOCD then assumed that the organised society would link up with the political actors for formal discussion of the matters. However, as noted later, this theoretical commitment by the ZHOCD was not practically fulfilled, as there was no deliberate and systematic way of engaging the political actors. The figure demonstrates the envisioned theory of change by the ZHOCD.

The lowest level is made up of communities that are immersed in poverty, fear, lack of knowledge, and other challenges. The second level is characterised by activities in civil society, researchers, and other non-state actors who are supposed to represent the interests of different groups found in the lowest stage. Yet, according to the ZHOCD, these actors are not coordinated for effective engagement of political actors at the top of the triangle. Thus, with an empowered base of coordinated middle-level actors, there will be a formal dialogue at the policy level whose outcomes are guaranteed of implementation. The envisioned theory of change fits well in Lederach’s conflict transformation theory that emphasises the creation of dialogue to build platforms of dialogue to build peace in society (Gumbo & Shava, 2021).

Source: Gumbo and Shava (2021:142)

METHODOLOGY

A historical approach was used to glean data for this study. The author documents a chronological narrative of the key events from 2017 to 2021. The key questions answered are: What is a national dialogue? Why is inclusivity important? How did ZHOCD ensure inclusivity in its national dialogue initiatives? Were the initiatives inclusive anyway?

A comprehensive literature review of the ZHOCD-selected pastoral letters issued between 2017 and 2021, and other strategic and programmatic materials produced, was conducted. Internet materials on national dialogues and academic work on the subject were also reviewed. Data collected through 25 key informant interviews (KIIs) for a separate project were also utilised. They were purposively selected to represent key stakeholder groups, including senior Church leaders from the ZHOCD, former members of the NCP and representatives from the main political parties. Interviews were conducted under the principle of non-attribution to encourage candid responses. The author’s roleas a former member of the ZHOCD secretariat was employed as a methodological lens of auto-ethnography, allowing for a reflexive analysis that combines experiential knowledge with critical academic distance. The unit of analysis was the ZHOCD, where its national dialogue was being analysed.

DISCUSSION OF KEY FINDINGS

The ZHOCD has been engaged in nation- building processes. However, the major highlights manifested when the ZCC, EFZ, and ZCBC produced a signature document named ‘Zimbabwe We Want Discussion Document’ in 2006. The document comprehensively defined the national problem and the way forward. The ZHOCD (2021:3) summarises the contents of the ‘Zimbabwe We Want Document’ as:

The spirit of the “Zimbabwe We Want Document” was embodied in its values of “Spirituality and Morality, Unity in diversity, Respect for human life and dignity, democratic freedoms, respect for other Persons, Democracy and good governance, participation and subsidiarity, Sovereignty, Patriotism and Loyalty, Gender equality, Social solidarity and promotion of the family, stewardship of creation, justice and the rule of law, service and accountability, promotion of the common good, option for the impoverished and the marginalised, and excellence.

The subsequent efforts by the ZHOCD were hinged on the 2006 document. When the new government of President Emerson Mnangagwa, ushered in by the military in 2017, was established, the Church took the opportunity to strengthen its nation-building role. The government characterised itself as a ‘New Dispensation’, and the President emphasised that the ‘Voice of the people is the voice of God’ (Vengesai, 2021). The leader of the main opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) Alliance, Nelson Chamisa, claimed that ‘God is in it’ in his campaign messages. Thus, the messages of the two major political parties motivated the Church to advocate for national dialogue. The Church wanted to build on the opportunity created by the public poster of the main political leaders, in which the latter presented themselves as prepared for national dialogue. However, challenges such as economic instability, political polarisation, and contested election outcomes persisted, manifesting in further social, economic, and political crises.

“Kairos” Moment: 2017 Statement

On 15 November 2017, the ZHOCD issued a statement in response to the overthrow of President Mugabe. It viewed the development as an opportunity for renewal in the nation. The statement read, “We have reached a new chapter in the history of our nation. Our God created everything out of chaos”. The ZHOCD defined the key challenges as mainly consisting of a loss of trust, caused by economic and social problems, further compounded by the violations of the national constitution. In addition, the statement opined that ordinary people’s interests were being ignored by the political leadership. The statement read:

All of us at some point failed to play our roles adequately. The Church has lost its prophetic urge, driven by personality cults and superstitious approaches to socio- economic and political challenges. Civil Society, over time, has become focused on survival and competition and lost the bigger picture of the total emancipation of the population. But the current situation is also a result of the many people in the ruling party who feel outdone, who enjoyed unbridled access to the trough of patronage. Journalists fanned the politics of hatred by giving it prime space in the name of sales and profits. All Zimbabweans must take some blame for our current situation (ZHOCD, 2017: 2).

The most important section of the statement was its call for a national dialogue, as evidenced by the excerpt below, which reads:

Finally, we are calling the nation to a table of dialogue. The current situation gives us an opportunity to reach out to each other. There is no way we are going to go back to the political arrangements we had some days ago. We are in a situation that cannot be solved by anything other than dialogue. This dialogue cannot only happen within the ruling party. What we need is a National Envisioning Platform (NEP) that will capture the aspirations of all the sectors of society. The church, alongside other stakeholders in the private sector, academia, and other spheres, can establish a NEP as an inclusive space to enable Zimbabweans from all walks of life to contribute towards a democratic transition to the Zimbabwe We Want (ZHOCD, 2017: 3).

While this marked the beginning of ZHOCD’s spirited call for national dialogue, the inclusivity of the envisaged process was not well articulated in the statement. The proposal for a NEP was not enough to define an inclusive process. It remained a vague statement. This probably explains why the new government ignored the Church by forming a ZANU-PF government without including other players who had helped topple President Mugabe, except the army generals who were thrust into various ministries. These include General Constantino Chiwenga (Vice President), General Sibusiso Moyo (Minister of Foreign Affairs), and Air Marshal Perrence Shiri (Minister of Lands and Agriculture).

The opposition and the civil society were not considered, thereby ignoring the ZHOCD proposal for an NEP. The ZHOCD had also called for a Transitional Government to facilitate the smooth landing of the new government, but this was not fulfilled. Thus, the country immediately went into an election mode, leading to yet another contested election result in 2018. Vengesai (2021) holds that from then onwards, ZHOCD efforts were compromised by the fact that the government characterised it as part of the regime change agenda.

National Prayer Breakfast Meeting

On 7 February 2019, the ZHOCD convened the ‘National Prayer Breakfast Meeting’ in Harare at the Harare International Conference Centre (HICC) to officially launch the national dialogue. This followed a series of bilateral meetings held between the political parties and the ZHOCD. The meeting was inclusive as it targeted the ruling party and the main opposition actors, civil society, students, farmers, vendors, the security sector, academia, independent commissions, the diplomatic community, and many more.

However, on 6 February 2019, President Mnangagwa convened a meeting for political parties that participated in the 2018 elections. The MDC Alliance did not attend as it called for a ‘genuine dialogue’. It was later noted that the Political Actors Dialogue (POLAD) was formed from that session before it was formally constituted in May 2019. This author viewed POLAD as a direct reaction to the Church’s envisioned process. Yet, the ZHOCD meeting at HICC was attended by over seven hundred people from different sectors (this author was the coordinator). President Mnangagwa apologised a few minutes before the official start of the meeting as he “had rushed to attend to the Vice President, Chiwenga, who was being taken abroad for medical treatment”. Leaders from other religious groups also attended the meeting. Critically for this paper, the Head of the Zion Christian Church, Bishop Nehemiah Mutendi, challenged the ZHOCD to “open up for Indigenous churches to join the platform”. One could view this call as a confirmation that some key players felt that the ZHOCD was exclusive in its approaches. A few months later, the Zimbabwe Indigenous Interdenominational Council of Churches (ZIICC) was formed as a para-church organisation composed of indigenous churches to engage collectively on national issues. The ZIICC demanded space in the national dialogue processes, and the ZHOCD initiated communication of the new organisation. The inclusivity of the ZHOCD initiatives was put to the test. The ZHOCD, however, celebrated the Prayer Breakfast Meeting as the beginning of an inclusive national dialogue process in Zimbabwe. The meeting stands as a formal attempt by the ZHOCD to be inclusive, yet it was contracted by later processes under the NCP.

Sabbath Call Proposal

The ZHOCD convened an Episcopal Conference for its members, from 8 to 9 May 2019 at the Large City Hall in Bulawayo. The major outcome of the conference was the Sabbath Call Proposal, which tabled the suspension of political contestations for “seven years,” during which the country would have to address all the noted challenges (ZHOCD, 2019). The Sabbath Call proposal was eventually published on 7 October 2019 at Synod House in Harare by the ZHOCD leadership. In promoting inclusivity, the ZHOCD shared the proposal with other key stakeholders, including President Emerson Mnangagwa and Nelson Chamisa, for input and/or adoption.

The key informants who participated in a separate project lamented that ZHOCD did not include civil society, academics, other faith actors, and even its lower structures when it made this critical decision. Thus, the ZHOCD was not inclusive in its initiatives. The proposal was received with mixed feelings by the public. Radical ZANU-PF activists directly attacked the ZHOCD. Yet other non-state actors gave the ZHOCD an ear and engaged with it on the proposal. On 19 October 2019, President Mnangagwa responded to the proposal through a letter in which he directly rejected the proposal, arguing that it was meant to rescue Chamisa, whom he described in the letter as an ‘ungracious loser’ (Mnangagwa, 2019). President Mnangagwa challenged the ZHOCD’s interpretation of the ‘Seven Days Theology’. Chamisa diplomatically rejected the proposal, arguing that it was unconstitutional and was against his party’s values (Chamisa, 2019). Thus, even though the ZHOCD had reached out to key stakeholders for the sake of inclusivity, its initiative was largely viewed as exclusive and unconstitutional.

Exclusivity of the National Convergence Platforms (NCPs)

Academia, civil society, and other interested individuals invited the ZHOCD for formal reflection sessions on the Sabbath Call proposal in October 2019. A series of meetings took place, resulting in the adoption of the NCP and its launch on 13 December 2019 at the ZCC premises. The launch event was attended by over a thousand delegates from across the country, representing civil society, academia, development partners, diplomats, traditional leaders, independent institutions, and other non-state and non-political actors. The ZHOCD was ‘inclusive’ in its invitation, yet it deliberately left out the political actors from the government and opposition parties. The rationale was to mobilise the non-political actors first for a strengthened voice when political parties were to be engaged. Political parties normally respect the numbers. The move, however, attracted fierce criticism from the political actors. The NCP was intended as a platform to host deliberations on social, economic, and political challenges (NCP, 2019). It brought together the ZHOCD, civil society apex bodies, the Citizen Manifesto, the National Association of Societies for the Care of the Handicapped, the National Transitional Justice Working Group, the Platform for Concerned Citizens, the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions, and the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum, which formally endorsed the NCP. The incorporation of different sectoral groups ensured the much-needed inclusivity and representativeness of the general population. Thus, the Church assumed that the composition was strategic enough to pursue national dialogues that would attract the attention of political parties. Yet, there was no concrete structural bonding among these actors, as noted later.

The subsequent establishment of the NCP structures, including the Coordinating Secretariat, manifested the exclusivity of the ZHOCD and its collaborating partners. The ZHOCD assumed the secretariat and chair roles. Other apex bodies led technical committees to spearhead conversations on specific issues, namely, national healing, constitutionalism and elections, economy and social contract, humanitarian, and international relations. A few months after the establishment of the technical communities, tension emerged between the civil society and the Church. The Church continued with its routine issuance of pastoral letters when the need arose. Yet, immediately after the publication of one of its statements, some members of the NCP raised concern. While the ZHOCD had ensured inclusivity by collaborating with other non- state and non-political actors, the former was viewed as not pursuing collective efforts. On 3 September 2020, the NCP issued a communication to the South African Convoy welcoming the engagement of the South African government with the Zimbabwe crisis, as well as noting the attention to Zimbabwe by the African Union. This did not save the NCP, which was now marred with irreconcilable reactions between the ZHOCD members and some members of the NCP, who accused them of being monopolistic in their approach.

Meanwhile, between July and September 2020, the ZHOCD convened bilateral and multi-party meetings advocating for national dialogue. This continued into the following year, leading to the issuance of the “National Consensus Call” (ZHOCD, 2021) calling for the nation to reflect on the national question. This development further confirmed the exclusivity of the ZHOCD since its contents could have been collectively communicated under the NCP banner. On the other hand, the ZHOCD did not engage the POLAD as a platform for national dialogue, further confirming its exclusivity and monopolistic tendencies (Gumbo & Shava, 2021). Meanwhile, ad hoc engagement of military officials, other faith actors, and the diplomatic community continued. The military, in particular, was not given the attention it deserved by the ZHOCD (Gumbo, 2023). A more systematic approach was needed to include the military in informal and formal engagement processes.

CONCLUSION

The paper has analysed the ZHOCD national dialogue initiatives from 2017 to 2021. It was noted that while the ZHOCD claimed to be pursuing an inclusive and comprehensive national dialogue, some of its approaches were generally exclusive. The study further noted that inclusivity does not always lead to effectiveness. The dynamics that manifested within the NCP confirmed that, indeed, inclusivity can also lead to ineffectiveness. The ZHOCD failed to consolidate its working relationship with some civil society actors. Moreover, it failed to mobilise the entire nation for national dialogue by being deliberately selective in its engagement processes. The engagement of the government remained unclear. This paper, therefore, recommends the ZHOCD to develop formal, systematic, and concrete engagement strategies for the government, political actors in general, and the military as key stakeholders in national dialogue. For instance, there is a need to adopt a model of core-chairing the platform where the Church and civil society second two leaders each as chairperson. This ensures shared ownership while also facilitating the building of trust among the members. To avoid overlooking some key actors, there is a need to institute a deliberate stakeholder mapping matrix at the initial stages. The paper noted that this mapping was not well done in the case of the NCP, leading to the exclusion of critical players such as the military. In future, there is also a need to establish a separate secretariat of the platform, which does not double as the secretariat for a member. This will ensure that the secretariat does all administrative and political liaison work without distraction. Lastly, there should be clear and deliberate lines of communication with political parties and the government to guarantee the implementation of agreed outcomes of dialogues.

REFERENCES

Center for the Advancement of Rights and Democracy. (2024). Inclusion and transparency in the Ethiopian national dialogue processes. https://www.cardeth.org/sites/default/files/END/Ethiopian%20National%20Dialogue%20Process-%20Activities%20Assessment%20Report%20I%20for%20Inclusion%20and%20Transparency%20%20%20(1.pdf

Chamisa, N. (2019). Call for national sabbath for trust and confidence building [Letter]. Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations. https://www.newsdzezimbabwe.co.uk/2019/11/chamisa-says-no-to-polls-sabbatical.html

Elayah, M., & Schulpen, L. (2016). Civil society’s diagnosis of the 2013 national dialogue conference in Yemen: Why did it fail? Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research Brief. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311739881_Civil_society's_diagnosis_of_the_2013_National_Dialogue_Conference_NDC_in_Yemen_why_did_it_fail

Gumbo, T. (2023). An evaluation of the Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations’ strategy of national dialogue to resolve Zimbabwe’s political challenges from 2006 to 2022 (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Africa University.

Gumbo, T., & Shava, C. K. (2021). Application of Lederach’s conflict transformation theory by Zimbabwe Council of Churches in national dialogue: An insider perspective. Africa Research Bulletin, 1(2), 134–148. https://afrifuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/tinashe-gumbo-collins-kudakwashe-shava.pdf

Mandikwaza, E. (2025). A conceptual framework for national dialogues: Applied theories and concepts. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 24(2). https://www.accord.org.za/ajcr-issues/a-conceptual-framework-for-national-dialogues-applied-theories-and-concepts/

Mnangagwa, E. D. (2019, October 19). Government response to the Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations’ call for national sabbath for trust and confidence building [Letter]. Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations Secretariat.

Mujinga, M. (2023). An analysis of the Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations’ call for a sabbath on elections. Stellenbosch Theological Journal, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.17570/stj.2023.v9n1.a27

National Convergence Platform. (2019, December 13). Press statement issued at the launch. https://www.ncp.org.zw/press-statement

Planta, K., Prinz, V., & Vimalarajah, L. (2015). Inclusivity in national dialogues: Guaranteeing social integration or preserving old power hierarchies? Berghof Foundation. https://berghof-foundation.org/library/inclusivity-in-national-dialogues-guaranteeing-social-integration-or-preserving-old-power-hierarchies

Stigant, S., & Murray, E. (2015). National dialogues: A tool for conflict transformation? (Peace Brief No. 194). United States Institute of Peace.

Inclusive Peace and Transition Initiative. (2017). What makes or breaks national dialogues (Briefing Note). Graduate Institute Geneva.

Vengesai, C. (2021). Ecumenical ingenuities as an instrumental political tool of conflict transformation in Zimbabwe’s new dispensation. National Dialogue Journal, 5(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.47054/RDC212037ch

Yohannes, D., & Dessu, M. K. (2020). National dialogues in the Horn of Africa: Lessons for Ethiopia’s political transition (ISS Report No. 311). Institute for Security Studies.

Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations. (2019). Sabbath call proposal. https://efzimbabwe.org/2019/10/document-call-for-national-sabbath/

Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations. (2021, February 21). National consensus call. https://www.facebook.com/ZimbabweCouncilofChurches/posts/the-zimbabwe-heads-of-christian-denominations-zhocd-national-consensus-call/1749367901904495/

Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations. (2017, November 15). Zimbabwe between a crisis and kairos (opportunity): The pastoral message of the churches on the current situation. https://familyofsites.bishopsconference.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/07/ZHOCD-statement-151117.pdf